- Home

- Bryan Hoch

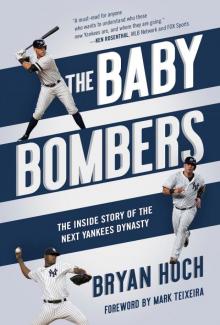

Baby Bombers Page 14

Baby Bombers Read online

Page 14

“I’ve been making adjustments my whole life,” Judge said. “I’ve been a work in progress for twenty-five years now. Every offseason, I’ve got something I try to work on.”

During that time, the number .179 was scalded into Judge’s consciousness. He programmed a note into his iPhone that displayed the unattractive batting average, making it one of the first things that he saw every morning.

“In some of the tougher times, you start to see players really doubt themselves,” Rowson said. “He’s one of those guys who never doubted himself. He stuck with it, he learned a lot from it, and instead of getting down about it, he figured out how to fix it. That’s what good players do.”

As spring training neared, Judge vowed that 2017 would be different. .179? Never again.

“It’s motivation to tell you, ‘Don’t take anything for granted,’” Judge said. “The game will humble you in a heartbeat.”

CHAPTER 8.

Spring Forward

George M. Steinbrenner Field serves as the Yankees’ home during the sun-splashed months of February and March, when spring training is in full swing. Once the team goes north, the field is entrusted to a group of athletes in their early twenties who comprise the roster of the Yankees’ Florida State League affiliate, while the upper levels of the stadium serve as the base of operations for a multi-billion-dollar corporation and the most recognizable brand in professional sports.

Every decision of significance either comes directly from or is vetted through Tampa, where Hal Steinbrenner can often be found in his fourth-floor office, perched high above the diamond. Though he’d served as the day-to-day control person of the organization since 2008, running the Yankees as a family business alongside his siblings Hank, Jennifer, and Jessica, the youngest of the Steinbrenners retained many interests outside of baseball.

He’d been passionate about the family’s hotel and horse racing ventures, held an affinity for aviation, and had earned a reputation around Major League Baseball as something of a meteorological savant, frequently using radar data to scan the skies from afar to determine if his team should prepare for a rain delay. Steinbrenner’s input saved one game of the 2009 ALCS against the Angels from being postponed, as he told the league that his data showed the storm would dissipate. It did, saving a considerable amount of money and headaches with television and ticketing.

Originally named Legends Field, the Steinbrenner Field facility sits adjacent to Raymond James Stadium—home of the NFL’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers—and was constructed to replicate the exact dimensions of Yankee Stadium, circa 1996. The windows lining Steinbrenner’s office provide a view of palm trees that sway with the traffic whizzing by on Dale Mabry Highway, a major commercial thoroughfare that connects Interstate 275 with fast food restaurants, big box retailers, auto dealerships, and more than a handful of adult entertainment venues.

It was here, shortly after the conclusion of the 2016 season, that Steinbrenner peered into a glowing computer screen and monitored the social media conversation surrounding his club. Most of Steinbrenner’s clicks summoned phrases of positivity, and the Yankees managing general partner smiled.

“This feels different,” Steinbrenner said. “I mean, we’ve got a great crop of good young players, and a good crop of veterans as well. It’s a great mix and I think the veterans are going to be great dealing with the kids, mentoring them. We’ve seen that in the past. But they’ve got to prove themselves, a number of these guys. This is their big chance and they’re going to get it this year.”

Steinbrenner had sensed the uptick in excitement in 2015, when the Yankees gave Greg Bird and Luis Severino late-season reps on the big-league stage, and that sentiment was reinforced in the weeks that followed the decision to retool the roster in July of 2016. With every “like” and retweet, Steinbrenner believed that the fan base was lending its approval to the new course.

Steinbrenner repeatedly mentioned Gary Sanchez and Tyler Austin as promising reasons to watch the Yankees in 2017, while also noting that he looked forward to tracking the progress of Clint Frazier, Ben Heller, Justus Sheffield, and Gleyber Torres, among others.

Chance Adams, Dustin Fowler, Jorge Mateo, James Kaprielian, and Tyler Wade also received hype, but no one had more placed upon his broad shoulders than Aaron Judge. Shrugging off Judge’s high strikeout rate during his first taste of the majors, Steinbrenner had boldly stated that he expected Judge to establish himself as the Yankees’ starting right fielder.

“He’s got some work to do. He knows that,” Steinbrenner said. “We’re going to figure out exactly what we think is wrong. My expectations are, he’s going to be my starting right fielder this year. That’s a big deal and a big opportunity. I know he’s going to make the most of it.”

The Yankees organized a “Winter Warm-up” event in January 2017 that introduced several of their youngest and untested players to the icy New York City streets. Adams, Frazier, Kaprielian, Sheffield, and Torres served lunch and danced with seniors at a Manhattan church, wandered the corridors of the Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum, sampled Italian delicacies along storied Arthur Avenue in the Bronx, and attended a Knicks game at Madison Square Garden.

For Frazier, the highlight of the trip was a private tour of the museum at Yankee Stadium, during which they were invited to hold one of Babe Ruth’s game-used bats, a jersey that belonged to Lou Gehrig, and a glove worn by Mickey Mantle. As he wandered the expansive Great Hall, a long corridor along the first-base side of the Stadium, Frazier couldn’t resist peeking out at the stadium grass and envisioning the opportunity to patrol those grounds.

“I don’t know when I’ll be there, but I’m happy to be here,” Frazier said. “I’m proud to say I’m a part of the Yankees organization. It’s the goal to make it up there this year.”

Joined by big league second baseman Starlin Castro, most of the prospects took part in a one hour “Town Hall” Q&A at the Hard Rock Cafe in Times Square, speaking to approximately 300 invited fans in an event that was live-streamed on the Internet. Cashman said that the event gave those players a chance to “sword fight a little bit” with the press, which could prove to be valuable experience down the line. The GM returned to his stadium office enthused about what was coming through the pipeline.

“We have a lot of quality, young, hungry talented players, and we still have some veterans mixed in here,” Cashman said. “I think if we stay healthy and perform up to our capabilities, I think we can start writing a new chapter in Yankee-land.”

Prognosticators generally held mixed views of the 2017 roster, with the Yankees expected to be in the early stages of a rebuild. Their big winter move had been to re-sign Aroldis Chapman to a five-year, $86 million deal, and Chapman created a stir during a conference call with reporters when he said that he believed Cubs manager Joe Maddon had “abused me a bit.” Chapman threw ninety-seven pitches in the final three World Series games, seeing a drop in velocity while blowing the save in Game 7 against the Indians.

“I believe there were a couple of times where maybe I shouldn’t be put in the game and he put me in, so I think personally I don’t agree with the way he used me,” Chapman said. “But he is the manager and he has the strategy.”

The Yankees’ other notable signing was to add thirty-seven-year-old Matt Holliday on a one-year, $13 million deal, intending to use the veteran as their designated hitter. The Yankees kept a small piece of their budget available and considered signing a pitcher to bolster their shaky rotation, but instead spent it on first baseman Chris Carter when his market crumbled. Despite leading the National League with 41 homers for the Brewers in 2016, Carter merited a one-year, $3.5 million contract––an indication of how teams’ views of big-swinging, strikeout-prone sluggers with low on-base percentages had changed.

At least on paper, adding Chapman, Holliday, and Carter—while trading Brian McCann to the Astros for a pair of teenaged pitching prospects—hadn’t drastically moved the needle from where the Yankees were at t

he end of 2016. Not one of eight Sports Illustrated writers picked the Yankees to win the American League East or a Wild Card in the publication’s preseason issue, while the stats-friendly website Fangraphs forecast them to finish last in the five-team American League East, with eighty-three losses.

“Somebody brought to my attention early in spring training, I think it was one of the writers, that we were predicted to be an 80-82 or an 81-81 team,” Brett Gardner said. “I thought we had a chance to be way better than that.”

Cashman also shrugged off the slights, believing that with health, the Yankees would be good enough to at least make a run at one of the AL’s two Wild Card slots.

“What sank us in 2016 was offense. It wasn’t pitching,” Cashman said. “A-Rod, Beltran, and Teixeira, that’s the middle of our lineup. They did not produce and our offense was one of the worst in the American League last year, which was unexpected. I thought, if you take those three guys at Triple-A—Bird, Judge, and Sanchez—and pop them three, four, five [in the lineup] for 162 games next year, it’ll significantly out-produce what we got from Beltran, Tex, and A-Rod.”

Many of the recent World Series winners fielded young players with veterans mixed in, and manager Joe Girardi said that it was a formula that had served the Yankees well during a lengthy run of consecutive winning seasons that started in 1993—twenty-four years and counting as of the spring of ’17, second only to the Yankees’ own thirty-nine-year winning streak from 1926–1964. He saw the Yankees as having adjusted to a landscape where players do not become free agents as soon as they once did, with many opting for the security of a long-term contract early in their careers.

“I think our young players are very talented, but talent is one thing, production is another,” Girardi said. “We believe that they are going to be able to produce. We will help them get through the tough periods, but we think that they can produce at a high level.”

Pitchers and catchers were scheduled to report to George M. Steinbrenner Field on Valentine’s Day 2017, with position players due a week later, but many of the Yankees’ brightest prospects were invited to Tampa early for what the organization called its “Captain’s Camp.” A four-week crash course devised by player development head Gary Denbo, Captain’s Camp evolved into something of a seminar on leadership in which some of the team’s greatest players were called upon to help shape the next generation of stars.

In 2017, Derek Jeter, Andy Pettitte, Jorge Posada, CC Sabathia, and Alfonso Soriano were among the recognizable names to address the Baby Bombers in a classroom setting at the club’s player development complex––all of them unpaid for their appearances. Pettitte said that he had been honored to be tapped as a resource, seeing the program as a natural extension of the Yankees’ star-studded roster of guest instructors.

During his own playing days, Pettitte recalled sharing the clubhouse with the likes of Yogi Berra, Whitey Ford, and Ron Guidry, readily-accessible icons of Yankees teams gone by. Speaking to the next generation of Bombers, Pettitte said that he tried to relay how he had dealt with adversity, the importance of preparation, and shared tips on how to handle the mental aspects of the game.

“I hope it helps somebody,” Pettitte said. “For me, it was the coolest to have Yogi and to see Whitey and to see Gator around, the guys that you knew were just kind of the Yankees legends when I was a young man coming up.”

Having spent so much of his career at the Himes Avenue facility, where Jeter was perennially among the team’s earliest arriving players, the Tampa resident opted instead to treat about twenty players and front office personnel to an off-campus dinner. No discussion topic was out of bounds, and much of Jeter’s advice centered on how to properly represent the Yankees and coping with the pressures of playing in the majors. Judge tried to absorb as much as he could.

“He was big into ‘stay even-keeled,’” Judge said. “You’re going to have those times where you’re going to go 0-for-20, 0-for-25, 0-for-30. You’ve got those months where you can’t get out and the ball looks like a watermelon, but just try to stay even-keeled and stick to the process. It’s a long process. If you have a bad April or a bad May, you might bounce back in June or July. Just keep the pace and focus on whatever you can do to help the team.”

Denbo said the concept for the Captain’s Camp was hatched in the wake of Jeter’s retirement, when officials had gathered in a Tampa conference room to brainstorm about which names might step up as the next prominent figures in the organization. A few times each week, the prospects’ routines of preseason conditioning and on-field workouts would be interrupted by a visit from a new voice. Former GMs, scouts, and media members were among those invited to offer perspectives otherwise unavailable to the prospects.

“We get to talk to a lot of old veterans and older scouts and a lot of our staff members about how they handle themselves on and off the field, how they respected the game, how they played the game,” Judge said. “That’s great. A lot of guys don’t get that opportunity to hear from a lot of great players like we have.”

It could be viewed as a positive sign that the most significant controversy of the spring revolved around Clint Frazier’s long locks. Frazier had several inches trimmed off the day before the Super Bowl, but the twenty-two-year-old still took the field for the team’s first full-squad workout with a healthy amount of red peeking out from under his ball cap. Frazier loved those curls; he’d been heartbroken when his parents made him chop them down as a seventh grader, and had vowed never to do anything so drastic again.

One of Clint Frazier’s first questions after being traded to the Yankees in July 2016 was, “Do I have to cut my hair?” The highly-touted outfield prospect was told that he did. (© David Monseur, MiLB)

Clint Frazier's first four big league hits were a double, homer, triple, and single, making him just the second Yankee to hit for the cycle with his first four hits. The other player was pitcher Johnny Allen in 1932. (© Arturo Pardavila III)

The media took notice, and Girardi initially laughed off the comments, joking that there were probably more than a few people in the clubhouse who would have gladly traded hairlines. But when the conversation trickled upstairs to ownership, Frazier relented and told Girardi that he would trim the mop more. The Yankees tried to put a positive spin on the moment, tweeting a photo of Frazier in mid-shear on the morning of March 10.

“Just after thinking to myself and talking to a few people, I finally came to agreement that it’s time to look like everybody else around here,” Frazier said. “It had started to become a distraction. I just want to play. That’s what I want to do. I like my hair, but I love playing for this organization more.”

In camp that day as one of the team’s guest instructors, Reggie Jackson recalled a terrific quote from Mariano Rivera, who once said that, “the pinstripes are heavy in New York.” Jackson said that he believed Frazier was beginning to feel that weight.

“When you first come here, I think it takes time for some of the younger people to understand the Yankee way,” Jackson said. “The whole organization has a feeling about continuing—and I can say this with respect—the way the old guard wanted it. The way the sheriff wanted it is how we want to continue to do things.”

The Yankees’ hair policy had been in place since 1973, shortly after a group led by Steinbrenner had purchased the franchise from CBS for the remarkable price of $10 million. Accounting for inflation, Steinbrenner’s purchase price was the equivalent of $57.9 million in 2017 dollars, twenty times less than what Jeter and controlling owner Bruce Sherman paid for the Marlins.

When the team stood along the baseline prior to the ’73 season opener, Steinbrenner pulled out a scrap of paper and jotted down the uniform numbers of players who needed an immediate trim. Those were handed to manager Ralph Houk, who reluctantly relayed the owner’s orders to Thurman Munson, Bobby Murcer, Sparky Lyle, and Roy White, among others.

Steinbrenner’s demands morphed into a written rule, stating that no player,

coach, or executive may display facial hair other than a mustache and that scalp hair may not be grown below the collar. Hall of Fame closer Goose Gossage’s distinctive look came as a direct result of those rules, as he shaved off a beard but left an exaggerated, bushy mustache. Though Girardi acknowledged that Frazier’s hair did not specifically violate Steinbrenner’s code, the manager said that he believed the 1973 edict still had value.

“It’s a tradition by a man that meant so much to this organization, and if it’s important to him and it’s important to his family, then it needs to be respected by all of us,” Girardi said.

Jackson’s input helped Frazier, and it was not the first time that Mr. October had come through for him. Following the trade from Cleveland, Frazier posted an underwhelming .674 OPS in 25 games with the RailRiders and was sent to continue his season in the Instructional League. A three week program that runs from late September into October, the circuit’s sparsely-attended games are played within the confines of chain-link fences on the back fields of Florida complexes.

Sensing that Frazier was struggling to find motivation within those serene surroundings, Jackson approached the prospect after a game and invited Frazier out for frozen yogurt. Frazier loaded into Jackson’s rental car, still wearing his full uniform as though it were a throwback to his Little League days. Frazier said that he didn’t recall discussing baseball with Jackson that day, but they both believed that they had connected on a personal level.

“I don’t know if I can remember back how I thought when I was twenty-two, but I sure as hell was a wild antelope in the woods, that’s for sure,” Jackson said.

Frazier had a more contemporary role model in Brett Gardner, whom he shadowed through drills early in camp, studying the veteran in hopes of applying something to his own game. Gardner said that it was only natural for a young prospect to attempt to better his play in such a fashion; he’d done so himself not that long ago with Johnny Damon, whom Gardner still credits for helping him learn how to be a major leaguer.

Baby Bombers

Baby Bombers![[No data] Read online](https://i1.freenovelread.com/i2/04/08/no_data_preview.jpg) [No data]

[No data]