- Home

- Bryan Hoch

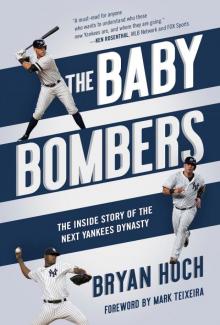

Baby Bombers Page 19

Baby Bombers Read online

Page 19

After being promoted to Class-A Charleston in 2013, the nineteen-year-old found that the challenges of facing professional hitters paled in comparison to the adjustments that were necessary to live on his own in the United States. In Tampa, Gulf Coast League players are provided with breakfast, lunch, and dinner, as well as bus transportation between the ballfields and the hotel.

Severino learned that no such amenities were provided in the South Atlantic League, so he had to learn how to do his own grocery shopping. He took crash courses via FaceTime from his mother and wife, Rosmaly. Before long, Severino and four of his teammates would take turns cooking and doing dishes, seasoning meat and rice with whatever spices they could find. Al Pedrique, Charleston’s manager that year, said that despite with the improving culinary skills, Severino still had a long way to go.

“You could tell that he wasn’t ready,” Pedrique said. “He was a young kid playing in front of crowds, night games, stuff like that. He realized that he was basically on his own and he needed to take care of himself off the field. That’s something that took him some time, to feel comfortable about taking care of himself off the field.”

In 2013, Luis Severino arrived in Charleston, South Carolina, wielding a fastball that approached the triple digits and a biting slider. The prospect’s biggest adjustments would take place away from the ballpark. (Courtesy of the Charleston RiverDogs)

Pedrique said that he saw Severino gaining comfort near the end of the season. Working diligently to learn English, Severino sometimes trailed a group of his teammates to a restaurant and let the American players order first, then tried to attach the word he’d heard to the food that arrived. There were many trips to McDonald’s and Burger King, and the first vocabulary words that stuck for Severino were “pizza” and “chicken sandwich.”

Re-runs of Friends also helped; Severino is one of several big leaguers from Latin America who discovered the long-running NBC sitcom could serve as a resource to pick up on the nuances of the English language. He laughed often, identifying Matt LeBlanc’s dim-witted but lovable Joey Tribbiani as his favorite character.

“How you doin’?” Severino would repeat.

To his teammates, Severino’s electric fastball and smooth mechanics transcended any language barriers. Tyler Wade played in the infield behind Severino during his 2014 season in Charleston, and was one of many teammates who marveled at his dominance.

“I was like, ‘This guy is throwing 100 [mph],’ and in Low-A guys aren’t really commanding their pitches,” Wade said. “Playing up the middle, I could see what signs were put down, and every time he’d get a sign down, he would literally hit the glove. I was like, ‘This is unbelievable.’”

In August 2015, the Yankees summoned Severino to the majors after a late-season injury to Michael Pineda. The boy who’d treasured the Yankees cap given to him by his father in the Dominican was now a young man issued a fresh New Era 59/50 model by the team, which he tugged toward his ears as he made his first walk to the mound at Yankee Stadium. Boston was the opponent that night, and thrilled by the opportunity to face fellow countrymen David Ortiz and Hanley Ramirez, Severino held his own by striking out seven over five innings in a 2–1 loss.

“That young kid, he’s got good stuff, man,” Ortiz said that night. “I think he’s going to be pretty good. I think at the end of the game he was missing location a little bit, but other than that, his stuff is very explosive.”

Making 11 starts at the end of that season, Severino experienced near-instant success, finishing 5-3 with a 2.89 ERA while helping the team reach the American League Wild Card game. That prompted the Yankees to guarantee Severino a place in the rotation at the beginning of the 2016 season, but he stumbled mightily, going 0-8 with an 8.50 ERA in 11 starts while bouncing between the disabled list, the minors, and finally the bullpen. Severino seemed to have lost trust in his changeup, and he had returned to being a more predictable fastball-slider pitcher. Opponents feasted, batting .337 off Severino in those starts.

“His command wasn’t as good and people saw it, especially in our division,” Joe Girardi said. “They knew who he was and they knew that he had a good fastball and a good slider, and so when you’re trying to get through a lineup a second and third time, you have to incorporate more than two pitches or you’d better be really, really good at locating your other two.”

The demotion was a wakeup call for Severino; instead of flying with the Yankees and staying at first-class hotels, he had returned to a world of eight hour bus rides that ended in the parking lots of the Fairfield Inns of the International League. Instructed to keep working on the changeup while with Triple-A Scranton/Wilkes-Barre, Severino went 8-1 with a 3.61 ERA in 13 games (12 starts), though he would later say that the pitch still didn’t feel quite right.

The Yankees called Severino up on July 25 as a reliever, and after two more tries in the rotation, decided to keep him in the bullpen for the rest of the season. He was 3-0 with a 0.39 ERA in eleven relief appearances, striking out 25 in 23⅓ innings, but both Severino and the Yankees still believed that his future would—and should—be in the starting rotation.

“2016, in the sample that he had, it was not something that you all of a sudden just pivot,” Cashman said. “This guy has the potential to be an ace and then 11 starts later, at age twenty-two, you’re going to all of a sudden just throw that out the door and say that’s not the case anymore? It was more of the noise that comes with being in a big market and trying to win. Development involves patience and he had to go through that process, for whatever reason.”

The Yankees had some theories. Cashman said that Severino may have hit the weights too fervently in the winter of 2015–2016, costing him flexibility. Pitching coach Larry Rothschild instructed Severino to lose some of that muscle mass, which they believed bumped up the velocity on his fastball and his changeup, eliminating the separation that permits a pitcher to fool big-league hitters. Severino reported to spring training at 216 pounds, down ten from the previous September, and said that he intended to win a spot in the rotation.

“I didn’t like the bullpen,” Severino said. “I always said I wanted to be a starter, and I went into the offseason determined to work to earn a spot. You can’t be a starter with two pitches. You have to have more than two pitches to be a starter.”

Unlike in 2016, there would be no guarantees. Cashman said that he viewed Severino as competing against Luis Cessa, Chad Green, Bryan Mitchell, and Adam Warren to fill the final two rotation spots, and if Severino was unable to win a spot, he would return to starting at the minor league level. That wasn’t going to happen. While Severino valued Rothschild’s input, he also suspected that someone of Pedro Martinez’s pedigree would have something useful to add.

“He figured we were very similar,” Martinez told Newsday. “He idolized me when I was pitching and he was a kid watching me at home. And he figured we look alike a lot and he wanted to actually correct some of the things that he was doing wrong, and I was able to help him out.”

The day of their first winter workout, Martinez had watched Severino throw on flat ground, then immediately dug into Severino’s mechanics, mound presence, and poise. Martinez observed that Severino seemed to sometimes lose his rhythm, then coached Severino to throw his changeup from the same angle as his fastball, something that Severino had tried without success to fix during the 2016 season.

A comparison of Severino’s motion between the 2016 and 2017 seasons reveals a subtle but important difference. When Severino started his motion in 2016, his arms sat belt-high, pushing both arms away from his body before moving his right arm back. In 2017, he still kept his hands belt-high, but moved his hands only slightly forward before moving his right arm back.

“I think that was the change that I made for this season, my mechanics,” Severino said. “[Martinez] told me that, if I change my mechanics a little bit, I’ll be more consistent in the strike zone.”

When Girardi learned that Severino had t

apped Martinez as a resource, he applauded the pitcher’s resourcefulness.

“Pedro had outstanding command of his fastball, an outstanding breaking ball, and an outstanding changeup,” Girardi said. “He had different weapons to get anyone out and he had more than one swing-and-miss pitch. I think anytime you have an opportunity to work with someone of his caliber who really knew how to pitch, that pitched inside very effectively, went deep into games—the mindset is so important in developing a pitcher like that.”

That was the poised approach that Severino brought to New York to begin his first full big-league season, determined not to let this second chance slip away. After taking a no-decision in his first start of the season at Baltimore, Severino put it all together on April 13 against the Rays in New York, striking out 11 while holding the Rays to two runs and five hits over seven innings. Martinez praised Severino’s slider and tempo from afar, tweeting, “So proud of this kid.”

Severino had absorbed a crucial lesson: velocity might get you to the majors, but intelligence was what kept you there. In a remarkable turnaround, Severino developed into the Yankees’ best homegrown starter since Ron Guidry, going 14-6 with a 2.98 ERA in 31 starts.

The twenty-three-year-old ranked third in the American League in ERA, fourth in strikeouts (230), ninth in innings pitched (193⅓), and tied for ninth in wins. His 10.71 strikeouts per nine innings were the highest in franchise history, and Severino’s teammates often remarked that they were glad they didn’t have to dig in against him.

“It’s filthy,” Judge said. “When he’s on, he’s got the good fastball command and his off-speed pitches are unhittable. That’s what I saw in the minor leagues for so many years. It’s just he’s attacking hitters, using his off-speed at the right time and that’s just what he does.”

Named to his first career All-Star team, Severino recorded his first five career double-digit strikeout games, becoming the second AL pitcher in the last forty-one years to post a sub-3.00 ERA with at least 225 strikeouts at age twenty-five or younger. The other was Roger Clemens, who did it in 1986 to win both the AL MVP and the Cy Young Award.

“We saw a bunch of really good starts pretty early on,” Girardi said. “[In 2016] he made some decent starts, but didn’t get any run support and I think it frustrated and it snowballed for him. He was dominant early on, and he was using his changeup, fastball. He was using up and down in the zone, where a lot of times last year he was mostly up and that’s when he was getting hit.”

Rowland had to be impressed by how far Severino had come. Severino’s fastball had been sitting between 89 and 93 mph on the afternoon his first professional contract was negotiated in December 2011, and now he was consistently among the hardest throwers in the majors, maintaining his strength deep into starts. In 2017, Severino equaled the highest average four-seam fastball velocity among big league starting pitchers, tying the Reds’ Luis Castillo (97.5 mph).

“We projected him with two plus pitches, an average pitch and above-average control, but nobody predicted the highest velocity fastball of all starting pitchers in the American League,” Rowland said. “That’s Mother Nature, that’s strength and conditioning, performance science, his personal work ethic, and commitment to excellence. I give him a heck of a lot of credit, I give our scouts a heck of a lot of credit. I give player development a heck of a lot of credit. It’s a team effort.”

Severino’s sixteen starts of one run or fewer led the majors, coming in a season in which Severino defeated Chris Sale, former Cy Young Award winners Rick Porcello and Felix Hernandez, and 2016 AL Rookie of the Year Michael Fulmer. Third baseman Todd Frazier said that one of the aspects of Severino’s games that his infielders appreciated the most was the speed with which he worked.

“When he’s working fast and he’s getting the pitch, when Sanchez puts whatever pitch he puts down, he’s like, ‘Let’s go, let’s do it,’” Frazier said. “That’s when he’s more devastating. That’s the best thing that can happen for us. Whether he’s giving up hits or not, we’re still in the game defensively because of how fast his pace is, for sure.”

CC Sabathia said that while the term “ace” tends to be thrown around loosely in many instances, Severino had earned it.

Luis Severino's 2.98 ERA in 2017 was the lowest by a qualified Yankees pitcher since David Cone (2.82) and Andy Pettitte (2.87) in 1997. (© Arturo Pardavila III)

“He’s got the stuff. His stuff is very electric,” Sabathia said. “His changeup has been a big key for him this year, throwing that into the mix. He throws 100 mph the whole game with a nasty slider and he throws that changeup in there.”

When the Yankees qualified for postseason play, it spoke volumes that Girardi lined up his rotation to have Severino start the win-or-go-home Wild Card game against the Twins. It was the first playoff game of Severino’s life at any level, and though his effort would end far too quickly, no one doubted that Severino would have more opportunities to showcase his stuff.

CHAPTER 12.

The Future is Now

The Yankees repeatedly downplayed the suggestion that 2017 was intended to be a rebuilding year, but there was ample evidence of how young they were. Joe Girardi’s lineup card for the April 2 season opener at Tropicana Field featured Gary Sanchez, Greg Bird, Ronald Torreyes, and Aaron Judge in the batting order—all of whom would still be subject to an under-twenty-five penalty fee if they had attempted to rent a car before leaving the Sunshine State.

It was the third time in franchise history that the Opening Day lineup featured four players under the age of twenty-five. In 1932, the Yankees had sent out a batch of kids: pitcher Lefty Grove, catcher Bill Dickey, third baseman Frankie Crosetti, and right fielder Ben Chapman. It had also happened in 1914 (first baseman Harry Williams, third baseman Fritz Maisel, shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh, and center fielder Bill Holden), and at twenty-eight years and 334 days, the average age of the Yanks’ Opening Day roster was its youngest in at least twenty-five years.

Beginning his tenth year as the Yankees’ manager, Girardi had grown accustomed to peeking around his office doorway to see a parade of established stars walking past, marching toward their round career milestone numbers and compelling cases for enshrinement in Cooperstown. Some of them, like the “Core Four,” had been teammates of Girardi. Others had been opponents. This was different for the veteran manager, surveying a crowd of fresh faces who could have been asking their parents for Beanie Babies or Tickle Me Elmos when Girardi was squatting behind the plate.

“We haven’t been this young in a long time, probably not since maybe 1996,” Girardi said. “It was a great mixture of youth and veteran players and guys that had a significant impact, guys that the fans recognized when they came up as homegrown and fell in love with players who did wonderful things. I think it’s going to be a very exciting year.”

It didn’t start that way. The Yankees dropped four of their first five games to the Rays and Orioles, and the mood in the visiting clubhouse at Camden Yards took another hit after the Saturday afternoon contest, when Sanchez sustained a right biceps strain after fouling off a 97-mph Kevin Gausman fastball. Their starting catcher, the AL’s most dangerous bat over the final two months of the previous season, would miss twenty-one games.

The Yankees were able to pull the emergency brake in the April 9 series finale; trailing by a run in that matinee, Judge tied the game with an eighth-inning homer off Mychal Givens and the Yanks added four runs in the ninth to secure a happy flight home.

“I think the turning point for us was in Baltimore,” Chase Headley said. “We had a chance to win both of the first two games there, and they came back to get us late. I thought that’s where it really started and we got off to a great start at home, and really played well the whole homestand.”

Taking the field for the Yankee Stadium home opener, the Bombers swept both the Rays and Cardinals in a pair of three-game series before taking two of three from the White Sox. The Yankees packed for their second road

trip having celebrated their best fifteen-game start in more than a decade, fattening their record with an 8-1 homestand that blended dominant starting pitching with jaw-dropping thump from the big bats.

It had taken until the season’s twenty-seventh game for the 2016 Yankees to post their tenth victory, when the calendar had already flipped into May. As the Yankees arrived in Boston for a rain-shortened two-game series later in the month, they had sent the message that they were not going to be pushovers in the AL East race.

“My brother called me after the first couple of weeks of the season and said that I sounded like I’d been shot out of a cannon,” said Suzyn Waldman, the Yankees’ longtime radio broadcaster. “It’s really changed everything around here. You smile more. They’re having fun. You’re watching them learn on the field. It’s just so refreshing. They laugh. They actually sit in the dugout and they laugh. They have a good time.

“I think the best part of it is they enjoy each other. For example, when I’ve talked to Sanchez about Severino, they talk about when they were in A-ball. I haven’t heard those conversations since Posada and Mariano were making fun of the skinny shortstop who arrived in 1991. We haven’t seen that. They all know each other very well. Judge and Bird, you listen to them have conversations. They go back, they’re all so young. Nobody is over twenty-five in the whole group. It’s tremendous fun.”

Masahiro Tanaka had another statement that he wanted to make. The Red Sox’s acquisition of Chris Sale had been the biggest move of the baseball offseason, popularizing the belief that Boston was going to be an unstoppable juggernaut. Cashman had wandered into that arena, opining in December that baseball had its new answer to the NBA’s star-studded Golden State Warriors.

Baby Bombers

Baby Bombers![[No data] Read online](https://i1.freenovelread.com/i2/04/08/no_data_preview.jpg) [No data]

[No data]