- Home

- Bryan Hoch

Baby Bombers Page 20

Baby Bombers Read online

Page 20

As Sale prepared to face the Yankees for the first time as a member of the Red Sox, having compiled an 0.91 ERA and 42 strikeouts in his first four starts for Boston, Tanaka privately told pitching coach Larry Rothschild that he intended to “beat the odds” against Sale.

Feeding the Red Sox a steady diet of two-seamers, cutters, splitters, and sinkers that were popped up or pounded into the ground, Tanaka outperformed Sale in a ninety-seven-pitch gem, recording his second career shutout in a 3–0 New York win. It would not be the last time that the Yankees watched Tanaka raise his game against an intimidating opponent.

“He mentioned that before the game, that he’s pitching against a really good pitcher, one of the better pitchers in baseball,” Rothschild said. “He was well aware of it. Any pitcher that’s a veteran and has had a lot of success is going to feel that way. You just rise to the challenge. You may win, you may lose, but you’re ready for it.”

The Yankees could shut down teams, and they could also outslug them. The next night in New York, the Yankees rallied from an eight run deficit to stun the Orioles with a 14–11 victory, with Matt Holliday hitting a three-run, walk-off shot in the 10th inning. Judge homered twice, Jacoby Ellsbury hit a grand slam, and Starlin Castro forced extra innings with a two-run shot.

Something special was happening, and Judge voiced the opinion that the big kids had been showing their baby Bronx brothers the way.

“I think it’s just the veteran squad we’ve got on this team,” Judge said. “I’ve learned a lot just watching them; how they prepare for the games, how they handle themselves during the game. We’ve kind of fed off Headley and Castro and Holliday. The at-bats they were having were amazing and fun to watch.”

The Yankees finished April with a 15-8 record, welcoming shortstop Didi Gregorius back to the lineup for the final three games of the month. Though Greg Bird was unable to recapture his spring performance before landing on the disabled list, the Yankees kept rolling.

An early May series at Chicago’s Wrigley Field cemented their never-say-die nature. On a frigid forty-five degree afternoon during which the wind blowing in from Lake Michigan necessitated ski caps and scarves, the Yankees had been iced over the first eight innings by Cubs pitching. Down to their final out, Brett Gardner dug out an 83-mph Hector Rondon slider and launched it over the bricks and ivy in right field for a three-run homer, giving the Yankees a 3–2 lead.

Gardner screamed as he sprinted around the bases and Aroldis Chapman—who’d received his World Series ring from the Cubs in an on-field ceremony a few hours earlier—rapidly warmed up to lock down the save.

“I think [I started to believe] maybe in April,” Gardner said. “We got off to a really, really good start without Didi, without Gary Sanchez. Seeing the way Severino was throwing the ball, seeing the start that Judge got off to, we knew we had a chance to be better than we expected to be. We lost [Michael] Pineda [to Tommy John surgery], but for the most part we’ve kept the majority of our team healthy throughout the course of the season."

To complete a sweep of the Cubs on May 8, the Yankees played another of their most memorable games, though it required all night to finish. Chapman coughed up a 4–1 lead in the ninth inning and the clubs played another nine innings—a videotaped Harry Caray led the fourteenth-inning stretch, singing ‘Take Me Out to the Ballgame’—before Aaron Hicks finally broke the tie, sliding home safely on a Castro fielder’s choice. The six hour, five minute contest featured more than 500 pitches from fifteen pitchers, with the clubs combining for forty-eight strikeouts, a new major league record.

“It showed that we’re going to grind out games,” Hicks said. “We’re going to fight to the end. They’re a great team, but we’re a good team too.”

Though he’d finished second in the spring right field battle to Judge, Hicks began to fulfill his five-tool promise, joining the growing crowd of cost-controllable twenty-somethings. An introspective switch-hitter with a cannon for a right arm from Long Beach, California, Hicks had landed in MLB after first envisioning his future in the PGA, spending much of his childhood driving and putting on the courses once traversed by a rising Tiger Woods.

Hicks’ father, Joseph, knew the disappointment that baseball could deliver all too well, his own career having stalled out in Double-A after seven seasons in the minors with the Padres and Royals, plus one more in Mexico. Hicks was born seven years later, and when his friends urged him to join the local Little League, his father told the natural right-hander he could play only if he agreed to bat left-handed.

The challenge did not steer Hicks away from baseball, improving his skills and helping him become a coveted prospect at Woodrow Wilson High School in Long Beach. Though Hicks stopped playing golf competitively at age thirteen, he still plays often during the offseason and has drawn curious glances from other golfers when showing off his ability to hit from both sides of the tee—thanks, Dad.

After batting .191 in his first 95 games as a Yankee, Hicks turned it on late in 2016. He had struggled to adapt to a part-time role, and believed that his consistency improved because the late July trades permitted him to log regular playing time.

“I always said that this kid had a chance to be a hell of a player,” said Ron Gardenhire, who managed Hicks in his first two big league seasons and will pilot the Tigers in 2018. “He was just a young guy that loved to be there, but he never understood what it took to be a big leaguer. I’m happy for him. I hope he continues it.”

A first-round selection of the Twins in 2008, Hicks’ tendency to rely on his natural talent exasperated the organization. There were occasions when Hicks arrived at the stadium not knowing if they were facing a left-hander or a right-hander that night, an inexcusable occurrence in an era where hours upon hours of scouting video are made available to every player.

There was evidence to suggest that Hicks had been hurried to the big leagues by Minnesota. Frustrated by his struggles against right-handed pitching, Hicks had entertained giving up switch-hitting before Hall of Famer Rod Carew was summoned to talk him out of it.

“I wanted to try to something new, and I wanted to help my team win,” Hicks said. “It was one of the low times of my career. Rod Carew actually called me and told me, what the heck am I doing giving up switch hitting? It’s a blessing, and that I should go back and work harder at it and learn from my mistakes. And he was right. I learned from my mistakes and I’m happy that I was able to change that.”

Carew and Hicks had worked out together in Southern California frequently during past offseasons. Torii Hunter, a nineteen-year big league veteran who returned to the Twins for his final season in 2015, regularly gave Hicks his version of tough love and pushed him to pay more attention to the mental side of the game.

Those flashes of progress prompted Cashman to believe that Hicks still could follow a career path similar to Jackie Bradley Jr., the talented Red Sox outfielder. Bradley hit .213 with a .638 OPS in his first 700 at-bats with Boston from 2013–2015 before breaking out as an American League All-Star in 2016.

“The talent package was recognizable and worth waiting on. Sometimes you have to walk through fire,” Cashman said.

The Yankees pushed their record to 21-9 after a May 8 victory at Cincinnati, standing alone in first place by a half-game in the AL East. As the Yankees adopted Bruno Mars’ funky “24K Magic” as their celebration song, thumping the track at window-rattling decibels following every victory, Girardi was ready to buy into the hot start.

“We’ve won in all different ways,” Girardi said. “We’ve won in games where we haven’t scored a lot of runs, we’ve won in games where we’ve scored late to take the lead. I think when you have power in your lineup like we have, you have the ability to win games and we’ve had to do that at times too. Our guys believe, and they should believe.”

As previously mentioned, New York’s June 11 matinee saw Judge hit the majors’ longest homer of 2017, a 495-foot drive off the Orioles’ Logan Verrett that came as pa

rt of a 14–3 victory. Judge would crush Baltimore pitching all year, and manager Buck Showalter joked that he wished the rules permitted him to position fielders in the bullpens while Judge batted.

“I can break it down all you want to, but he’s a big, strong man who puts some pretty good swings on baseballs and is making guys pay for a lot of mistakes we’re making,” Showalter said. “I don’t feel like he’s picking on us. He’s been doing it to everybody.”

At the conclusion of the day’s business, Judge led the AL in all three Triple Crown categories, batting .344 with 21 homers and 47 RBIs. Miguel Cabrera had been the most recent big leaguer to win one, doing so in 2012 for the Tigers, but Judge said the thought hadn’t crossed his mind.

“Not really, especially when you hit .179 the year before,” Judge said.

After winning five of six from the Red Sox and Orioles, the Yankees traveled to the West Coast on June 12, where their record improved to 38-23 with a 5-3 victory over the Angels in Anaheim. That victory gave New York a season-high four-game lead in the AL East, but the rest of their California adventure went miserably. They dropped the next two contests to the Halos and were swept in a four-game series by the Athletics, a series marked by Matt Holliday’s absence due to a mysterious illness that was later revealed to be the Epstein-Barr virus.

“The sun will come out,” Dellin Betances said during the seven-game losing streak. “We haven’t really been talking too much about it. We’ve been playing good ball. Those games, we’ve been close.”

With Headley struggling to provide offense at third base, the Yankees thought they might have a reinforcement in Gleyber Torres, but that option was dashed by an ill-advised headfirst slide into home plate. The Yankees’ top position player prospect, Torres was promoted to Triple-A shortly after vice president of baseball operations Tim Naehring passed through Trenton and reported to Cashman, “This guy is ready to go from my perspective, any time you want.”

Torres continued to enjoy success against more established competition, batting .309 with two homers and 16 RBIs in 23 games in the minors’ highest level, but his season ended in the fourth inning of a June 17 game in Buffalo, New York. Attempting to score from second base on a Mark Payton single to right field, Torres dove awkwardly into the plate, tearing the ulnar collateral ligament in his left (non-throwing) elbow.

The Yankees said they expected Torres to make a full recovery for spring training, but the injury dashed any chance of him making his big-league debut before 2018.

"He conquered the Eastern League for the period of time he was there, and he was starting to conquer the International League," Cashman said. "The way his trajectory was going, I think you would have seen him in the big leagues at some point. You may very well have seen him as the third baseman or the DH. It may have prevented us from trading for Todd Frazier, who knows? We never did find out, because he didn’t get more time."

• • •

Ronald Torreyes delivered another season highlight on June 23, with the smallest Yankee drilling his first career walk-off hit nineteen minutes after midnight to end a 2–1, 10 inning duel against the Rangers. It was the second win in ten games for the scuffling Yanks.

The evening had featured an elite matchup between Masahiro Tanaka and Yu Darvish that was beamed to millions watching early on a Saturday morning in Japan—“Breakfast at Wimbledon; Breakfast at Yankee Stadium,” Girardi had quipped. Following a 102-minute rain delay, Tanaka was ahead of the Texas lineup all night, registering two first-pitch balls. Tanaka needed an outing like that one. He’d been 0-6 with an 8.91 ERA in his previous seven starts, permitting 33 earned runs in 33⅓ innings.

“I was excited going into the game,” Tanaka said, “but once the game starts, then you’re not actually going against Darvish. You’re going against the Texas lineup. My focus was on every batter, every pitch. I think I was able to throw with good conviction. I’m really happy with the results.”

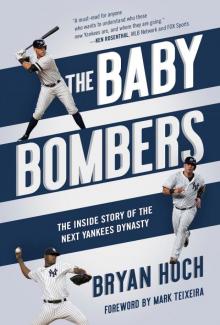

Masahiro Tanaka signed with the Yankees in 2014 after a standout career in Japan, where he was 99-35 with a 2.30 ERA in 175 games for the Tohoku Rakuten Golden Eagles. (Photo Credit: Hayden Schiff, CC BY 2.0 license)

A Gary Sanchez passed ball allowed the Rangers to grab a late lead, but Gardner answered with a ninth inning homer and Sanchez atoned with a one out hit in the 10th, scoring the winning run on Torreyes’ clean single to center field.

“I just have the mindset that at any given moment, they’re going to need me and I’ve got to be ready,” Torreyes said through an interpreter.

Five days later, Miguel Andujar went from the airport to the history books, becoming the first Yankee to collect at least three hits and three RBIs in his debut as he powered a 12–3 victory over the White Sox in Chicago. Signed out of the Dominican Republic at age sixteen, Andujar still carried some questions about his defense at third base, one week after he had been promoted from Double-A. His bat sure looked big-league ready. Stepping in as the DH in place of the ailing Holliday, the free-swinging Andujar went 3-for-4 with four runs scored, collecting a double, walk and steal.

“I’m never going to forget this day,” Andujar said through an interpreter. “Going out there for the first at-bat, I felt a little nervous. It’s my first at-bat in the big leagues. Following that at-bat, everything was normal again.”

The Yankees got another glimpse of the future in early July when Clint Frazier was tapped on his shoulder by RailRiders manager Al Pedrique, who led the twenty-two-year-old outfielder into the visiting manager’s office at McCoy Stadium in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. As the door shut, Frazier thought to himself, “This is it. I’m going up.”

Then, as Pedrique rattled off a straight-faced list of things that Frazier still needed to improve upon, Frazier wasn’t quite so sure about the purpose of this chat. Frazier finally exhaled when Pedrique concluded his sermon, telling Frazier that he could begin to work on those things the next day in Houston, where he would become the latest Baby Bomber to arrive in The Show.

“It was a bittersweet moment,” Frazier said. “There was a lot of truth to what he was saying; that I need to continue to work my defense, my base-running, and just focus on being a good teammate in the clubhouse, and just be all ears while I’m here. Those are things that it’s not bad to be reminded on. I’m glad we had that conversation.”

Reflecting on the interaction months later, Pedrique said that he sensed Frazier had put too much pressure on himself early in his Yankees tenure, trying to live up to the glowing scouting reports while proving to the organization that he was ready to play in the big leagues.

“When I told Clint, ‘You’ve got to be a better teammate,’ my point was that you’ve got to communicate with everybody, whether you have a good game or a bad game,” Pedrique said. “It’s a team. My advice to him that time was make sure you communicate with your teammates. You’ve got to feel like you want to be in the clubhouse. That’s where you spend most of your time, with your teammates, whether you’re on the road or at home. That’s like your second family. So you need to open up more, you need to relax, you need to enjoy the game on the field and off the field.”

Frazier credited many people, including Reggie Jackson and Matt Holliday, for helping him make the necessary adjustments to wear a big-league uniform. Holliday had spent time with Frazier during spring training, developing a friendship that kept them in text message contact during the first months of the regular season. While he tried to heed Pedrique’s advice, Frazier added that he still wanted his personality to shine through on the big stage.

“I think if I clip my own wings, I’m not going to be able to play the way that I want to,” Frazier said. “I think for me, as long as I can be myself without being a distraction or cause harm to the clubhouse or the team, I think I’ll be in good shape.”

Frazier made an immediate impact, becoming the twelfth Yankee ever to homer in his big-league debut, and the first since Tyler Austin and Judge hit their back-to-back blasts the previous August. Frazier’s first h

it was a sixth-inning double off Astros right-hander Francis Martes that eluded left fielder Marwin Gonzalez, sparking a five run inning.

His parents, Kim and Mark, had made the trip from Georgia for the game, and Kim shed tears when Frazier’s seventh-inning line drive landed in the Crawford Boxes over the left-field wall for his first career homer. Frazier said that he gave the ball from his first hit to his mom, and the home run to his dad.

“My parents are my role models, and my dad is my hero,” Frazier said. “For me, to go out there and have this kind of first game for him is really special for the whole Frazier family.”

Embracing his nickname of “Red Thunder,” six of Frazier’s first seven hits went for extra bases. He rescued the Yankees in the ninth inning of a July 8 game against the Brewers, crushing a walk-off, three-run homer in what was Frazier’s sixth career game.

“It’s just cool to be on the same plane as all of these guys,” Frazier said. “I keep telling people, ‘I went from eating Domino’s and Waffle House after the games in the minor leagues and now I’m eating steak on the plane.’ It’s the New York Yankees, man.”

As exciting as Frazier’s brand of play proved to be, he had not been the Yankees’ first choice to grab a spot in the outfield. That had been Dustin Fowler, whose season cruelly ended June 29 on Chicago’s South Side. As he pursued a foul pop-up down the right field line in the bottom of the first inning, Fowler’s right knee slammed into an exposed metal electrical box when he flipped into the seating area. He would be diagnosed with an open rupture of his right patellar tendon.

Like Archibald “Moonlight” Graham, the turn of the century New York Giants outfielder whose one and only big-league game in 1905 inspired a character eighty-four years later in the movie Field of Dreams, Fowler had played defense for half of an inning without having the chance to bat. Brett Gardner said it was “one of the worst things I’ve seen on a baseball field,” and Girardi hid his tears while he called for the cart that transported Fowler off the field.

Baby Bombers

Baby Bombers![[No data] Read online](https://i1.freenovelread.com/i2/04/08/no_data_preview.jpg) [No data]

[No data]