- Home

- Bryan Hoch

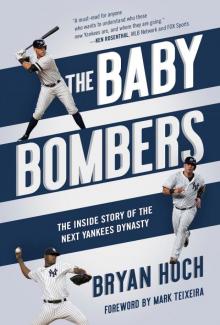

Baby Bombers Page 3

Baby Bombers Read online

Page 3

Now, with no instructions coming from the dugout, Meek fired an 86-mph cut fastball on which Jeter deployed his trademark inside-out swing, slashing a hard grounder that rocketed past first baseman Steve Pearce. Richardson took off, digging as quickly as his legs could carry him. A product of the Bahamas who scored a grand total of four runs in the big leagues, he was about to become the answer to a trivia question. Right fielder Nick Markakis scooped the ball and launched a rocket to catcher Caleb Joseph, who couldn’t handle the throw as Richardson swiped his left hand across home plate.

“The crowd went nuts,” Meek said. “In that situation, you just can’t be upset about that kind of thing. It’s bigger than all of us. It was just a great moment. A great moment for the game and him. There’s no better way for him to go out. It was just an amazing moment.”

Miles upon miles away, as he enjoyed some downtime before reporting to an upcoming assignment in the Arizona Fall League, Aaron Judge sat up and cheered.

“I was watching it in bed,” Judge said. “I got goosebumps, I remember, watching that game. Seeing how it unfolded, and of course it would just so happen to be that he’s coming up with a guy on second base. His signature hit to right field. It was crazy.”

Jeter raised his fists toward the sky and leapt, in what he’d later describe as “an out of body experience.” It created a magnificent photograph that would be reproduced thousands of times to appear in living rooms, studies, and bedrooms across the tri-state area, peddled with Jeter’s swirling signature in silver Sharpie for the low, low price of $799.99 (plus $165 if you wanted it framed).

The Orioles remained in their dugout to watch as the crowd serenaded Jeter, who embraced family members, former teammates, and others before making a slow solo walk to his position. While Sinatra crooned, Jeter’s spikes nestled into the soft lip of the outfield grass and he stole a moment.

Derek Jeter was a fourteen-time AL All-Star, a five-time Gold Glover, a five-time Silver Slugger, and a two-time Hank Aaron Award honoree, among other plaudits. Yet Jeter was most proud of his five World Series rings with the Yankees. (© Lawrence Fung)

“I wanted to take one last view from short,” Jeter said. “I say a little prayer before every game, and I basically just said thank you, because this is all I’ve ever wanted to do and not too many people get an opportunity to do it. It was above and beyond anything I’d ever dreamt of. I mean, I’ve lived a dream.”

That marked Jeter’s final game playing shortstop, though he would bat in two more games before ending his career with 3,465 hits, sixth all-time and the most ever by a Yankee. Jeter finished as a lifetime .310 hitter, the last at-bat yielding a dribbler of an infield single at Fenway Park that third baseman Garin Cecchini couldn’t pick cleanly.

“He didn’t say anything; he just tipped his cap at me,” Cecchini said. “I tipped my cap right back at him. I’ll always remember that for the rest of my life. I wasn’t trying to give him a hit. I was trying to make a play, because you don’t think about that. But after the fact of what happened, you think, ‘Oh man—that was the last hit of Jeter’s career.’”

• • •

The Yankees faced an identity crisis as they headed into the 2014–15 offseason. For two decades, they had been synonymous with Jeter, a marriage that began in a more innocent time when Jeter could still comfortably ride on a New York City subway without being noticed. Their impressive string of winning seasons dating to 1993 remained intact, and Gardner, Robertson, Sabathia, and Teixeira were still around to represent the last World Series-winning club. Alex Rodriguez was also set to return to the lineup after serving a historic 162-game suspension for performance-enhancing drug use.

The Steinbrenner family had authorized the expenditure of nearly a half-billion dollars on star power, pursuing right fielder Carlos Beltran, center fielder Jacoby Ellsbury, catcher Brian McCann, and right-hander Masahiro Tanaka. Those fresh faces had the potential to add sizzle and help the turnstiles click, but who were the Yankees without Derek Jeter?

They were about to figure that out.

“Who’s going to become the next great Yankee that people really latch onto?” Girardi said then. “I’m curious to see how it develops.”

CHAPTER 2.

The Knighted Successor

The Landmark Building is a commercial office tower that rises twenty-one stories above the city of Stamford, Connecticut, and on a clear day, the southwestern corner of its roof provides a panoramic vista of the Manhattan skyline. Each December, the facility’s management team hosts a “Heights and Lights” holiday festival where Santa Claus and his celebrity helpers make a rappelling descent to street level as the prelude to fireworks and a tree lighting ceremony.

It was a blustery, gray morning as Brian Cashman yanked down on the elf cap covering his head and peered at the passing traffic below, preparing to attach a rope to his belt and dangle off the side of the structure once again. Having been somewhat reluctantly named the Yankees’ general manager in February 1998, Cashman had outlasted his competition and now held the title of baseball’s longest-tenured person in that position. He had recently discovered that these types of adrenaline-inducing adventures provided a welcome release from one of the most demanding day jobs in all of professional sports, once saying, “I call it living.”

During spring training in 2013, Cashman had tried skydiving with the Army Golden Knights, flawlessly executing a tandem freefall from 12,500 feet. He had accepted when offered a second jump that afternoon, and that one did not go as well; thanks to a landing that Cashman jokingly compared to one of Paul O’Neill’s ugly slides into second base, Cashman sustained a broken fibula and a dislocated ankle. The injury required the installation of a plate and eight screws.

While being transported to the hospital, Cashman said that he could hear the late George Steinbrenner’s voice barking in an inimitable staccato: “You’ve got to get back to Tampa.” He had no regrets about the experience, saying that he was pleased the jumps had generated additional publicity for the Wounded Warrior Project. Cashman has thus far declined to open another parachute, preferring his death-defying activities to at least include some sort of anchor.

A momentary escape was welcome now. Cashman was being tasked with restoring the Yankees’ luster after missing the postseason for a second consecutive season––the first time they had done so in a non-strike season since 1992 and 1993, the conclusion of a twelve-year playoff drought. Compared to the challenges that waited in the Bronx, spending a few hours this 2014 holiday season helping Jolly Old Saint Nick liberate a bag of toys from the Grinch seemed to be a pleasant diversion.

In previous years, Cashman had welcomed any media members hardy enough to wake up in time for his 6:00 a.m. practice rappels, rewarding guests with a stream of quotes that served to warm baseball’s often dormant Hot Stove season. This time, however, the building’s public relations department issued a tersely-worded e-mail that indicated Cashman’s only availability would be following the event on Sunday evening. By then, most of the reporters covering the team would already be on their way to the Winter Meetings, an annual gathering of the sport’s decision-makers that was being held at the stylish Manchester Grand Hyatt resort in San Diego.

Though Cashman would acquiesce and offer public comments of little consequence that morning, he had a good reason for not wanting to be quoted on the record, preferring radio silence to dodges and fibs. Over the past several weeks, Cashman had been attempting to orchestrate a trade to pluck shortstop Didi Gregorius from the Arizona Diamondbacks, and the tea leaves indicated that he was finally nearing the finish line on a three-team deal that would deliver Derek Jeter’s replacement.

Regarded as an excellent defender with a strong throwing arm, Gregorius was available this trade season due in part to some lingering questions about his offense. As a twenty-four-year-old, Gregorius had batted .226 with six home runs and 27 RBIs in 80 games for Arizona, which on its face did not exactly make him the prime candidate t

o claim Jeter’s place in the field. The Yankees’ scouting and analytics departments looked past those raw digits, believing that Gregorius was capable of more than he had shown.

Cashman said that he had several trusted voices encouraging the pursuit of Gregorius, who had been seen and touted by at least six Yankees scouts in recent months. The most vociferous supporter was Tim Naehring, who had enjoyed a solid eight-year run as a Red Sox infielder before a torn right elbow ligament ended his playing career in the summer of 1997. Even as the input of Ivy League-educated numbers crunchers increasingly influenced front office decisions, Cashman seldom made a move without seeking Naehring’s input.

A Cincinnati native, Naehring found a comfortable landing spot in the Reds’ front office in 1999 before the sale of the team prompted a house-cleaning purge in late 2005. Naehring landed with the Yankees in 2007 and was primarily tasked with scouting players in the National League. His accounts of Gregorius had been overwhelmingly positive.

“I saw some things offensively that I thought were untapped,” said Naehring, who was promoted to a role as the Yankees’ vice president of baseball operations in 2016. “There were times where I saw the actual swing, he was making a bunch of adjustments with the setup of his swing. There was some late bat movement. There were some things where I thought if we could assist him and get him into a little better position to hit, I thought there was upside with hitting for average.”

Naehring said that as the Yankees dug deeper on Gregorius, they uncovered convincing reports about him as a person, while his work ethic had been evident in watching him play. Eric Chavez, a six-time Gold Glove Award winner with the Athletics who played third base for the Yankees in 2011–2012, had been one of Gregorius’ teammates for two seasons in Arizona near the end of his playing career. During a brief stint as one of Cashman’s special assistants, Chavez also opined that the Yankees should take a crack at acquiring Gregorius.

“I was really high on him,” Chavez said. “His defense is unbelievable, and hitting-wise he has the potential to be a good hitter—[I saw] a good .275, .280 hitter, 12 to 15 home runs. His swing plays perfect for Yankee Stadium; he’s kind of got that pull swing.”

It would turn out that Chavez had actually underestimated Gregorius’ power, but Cashman was sold. He recalls making at least ten different pitches to Arizona general manager Dave Stewart, a former star right-hander who carried the nickname “Smoke” and was the MVP of the 1989 World Series with the A’s. Each offer was rebuffed, as Stewart scanned the Yankees’ farm system and told Cashman that he could not find a match between the clubs. Frustrated, Cashman changed course, recalling that the Tigers had contacted the Yankees earlier that winter as part of their quest to secure a young starting pitcher.

Detroit general manager Dave Dombrowski had been particularly interested in Shane Greene. A twenty-five-year-old right-hander from Daytona Beach, Florida, who had compiled a seemingly ordinary minor league career, Greene emerged from the 15th round of the 2009 draft to become a surprise contributor down the stretch for the Yankees in 2014, leaning on a power sinker to go 5-4 with a 3.78 ERA in 15 games (14 starts) at the big-league level. Two of those starts had come against the Tigers, in which Greene permitted two runs in fifteen innings.

“They called us a couple of times,” Dombrowski said. “[Cashman] said, ‘If you have any way to get Gregorius from Arizona, we would trade Greene for him.’ So, I made contact with Arizona at that point to see if we could make anything work.”

Though the Yankees were reluctant to part with Greene, cognizant of the inflated value of starting pitching in the open market, Cashman decided that Gregorius was worth the gamble. During his days as the team’s assistant farm director, Cashman had absorbed the advice of front office mentors like Gene Michael, Bill Livesey and Brian Sabean, all of whom stressed that championship teams needed to have a “strong spine” up the middle. That phrase kept running through Cashman’s mind while he pursued the Gregorius deal.

“Everything needs to be working––from the catcher to the middle of the infield and center field,” Cashman said. “With Jeter, toward the back end of his career, he wasn’t the same player. No one is. So now we had a void at shortstop to fill. I didn’t have a shortstop, bottom line. Unfortunately, it wasn’t going to come from within; we didn’t have somebody waiting in the wings ready to go. It’s not like we hadn’t tried––we failed in that category, so now we were forced to go to the market and trade for somebody if we could.”

The Tigers accepted Greene from the Yankees, then flipped left-handed pitcher Robbie Ray and infielder Domingo Lebya to Arizona, a sequence that delivered Gregorius to New York. Stewart said at the time that Gregorius had been one of the D-backs’ most requested trade chips, but Arizona was comfortable drawing from their middle infield depth in exchange for Ray, who would struggle in his first two seasons in the desert before going 15-5 with a 2.89 ERA as a National League All-Star in 2017.

Baseball executives often say that trades can only be properly evaluated in years, not days or months, and Greene’s introduction to Detroit served as a perfect example of that axiom. Greene won his first three starts in a Tigers uniform, compiling a 0.39 ERA which invited suggestions that the Yankees might have made a costly mistake. When hitters adjusted, Greene tumbled hard. He finished 2015 with a 4-8 record and 6.88 ERA, and Detroit moved him to the bullpen for the following season. He remained there in 2017, finishing 71 games with a solid 2.66 ERA and nine saves for the last place Tigers.

“The tough decision-making in that process was that we were pitching deficient, especially starting pitching,” Cashman said. “It was going to cost us a guy that we did like in Shane Greene, who was a young, under-control starter. You’re robbing Peter to pay Paul, but it speaks to how important the shortstop position is. We held our breath and made the decision to do so.”

When Cashman called his manager to tell him that the deal had been completed, a highlight popped into Joe Girardi’s mind. Gregorius had hit his first big league homer against the Yankees in April 2013, jumping on a fastball to take right-hander Phil Hughes deep over Yankee Stadium’s right-field wall. It was Gregorius’ first at-bat as a Diamondback and at the time, Girardi said that he had wondered, “Who’s this kid?”

Had Girardi dug into the wiry athlete’s background that evening, an intriguing story would have emerged. While fans often spoke of Jeter as though he were royalty, Gregorius actually had the credentials, proudly carrying the title of “Sir Didi.” In 2011, Gregorius and most of his teammates were called to a state building in Curacao for a formal ceremony in which they would be knighted as members of Order of Orange-Nassau, their reward for being part of the Netherlands club that defeated Cuba in the IBAF Baseball World Cup.

“Instead of giving us money, they decided to just knight us, all the guys that had a clean record,” Gregorius said. “I’m happy to say it out loud every day.”

Born in the Netherlands, Mariekson Julius Gregorius moved to Curacao at age five and began answering to the nickname “Didi," which created some confusion in his household. Gregorius’s father, Johannes, and his older brother, Johnny, also favored the nickname, which necessitated qualifiers like “Didi Dad” or “Didi Son” at family gatherings. The three even played on the same semi-pro baseball team for two summers in the early 2000s, where they were referred to as “Didi Sr.,” “Didi Jr.,” and “Didi Little.”

Didi Sr.’s trade was carpentry, but he had also been a top pitcher for more than two decades in Curacao and the Netherlands. Gregorius’ mother, Sheritsa, played for the Dutch national softball team, and the couple has a treasured photo that shows the future shortstop, probably two years of age, wandering on a ball field with a bat in his hand. Around age seven, he’d comprised one half of a stellar Little League double play combination with Andrelton Simmons, who’d go on to win Gold Glove Awards with the Braves and Angels. Gregorius also played basketball and soccer, and swam competitively as a youth, even dabbling in speed skatin

g at one point, but baseball powered the Gregorius household.

An accomplished artist and computer whiz who regularly edits videos and paints on road trips, Gregorius quickly earned a reputation as the go-to person in the Yankees’ universe for tech support. Alex Rodriguez often asked Gregorius to tweak his iPad and once referred to him as “the modern-day Bill Gates who plays shortstop.”

Carrying a polymath background scarcely found in big league clubhouses, Gregorius speaks four languages—English, Spanish, Dutch, and his native Papiamento, plus fluent “emoji.” In a move that would endear him to the fan base, Gregorius soon composed celebratory tweets after each team victory, representing each contributor with a different cartoon graphic while adding the hashtag #StartSpreadingTheNews.

Years before he’d tag his teammates with hieroglyphics like clown face (Brett Gardner), bow and arrow (Jacoby Ellsbury), and boxing glove/carrot (Clint Frazier), Gregorius said that his earliest sketches began appearing in the margins of his school notebooks around age 10, occasionally drawing the ire of his teachers.

Even from afar, Gregorius had been touched by the drama of Jeter’s retirement, experiencing a rush of inspiration late in 2014 that prompted him to pull out his charcoal pencils. In one six-hour session, Gregorius painstakingly sketched Jeter doffing his batting helmet to a Yankee Stadium crowd. He posted the results of his effort on Twitter.

“That’s one thing that I really like,” Gregorius said. “When you sit down for an hour without the TV on, see what you’re going to do in those situations. I always get the drawing book.”

Baby Bombers

Baby Bombers![[No data] Read online](https://i1.freenovelread.com/i2/04/08/no_data_preview.jpg) [No data]

[No data]