- Home

- Bryan Hoch

Baby Bombers Page 4

Baby Bombers Read online

Page 4

The Reds signed Gregorius out of Curacao for $50,000 in 2007, the same year that Cincinnati drafted infielder Todd Frazier in the first round from Rutgers University. Frazier, who would be reunited with Gregorius on the Yankees in 2017, recalled that the lithe Gregorius had been a “skin and bones” teenager who had yet to discover the benefits of weight lifting. His minor league high in home runs had been seven, which he reached twice.

Gregorius made his big-league debut with the Reds in September 2012, notching his first hit with an infield single off the Astros’ Wesley Wright. Cincinnati traded Gregorius as part of a three-team deal with the D-backs and Indians three months later, and Arizona general manager Kevin Towers did not attempt to conceal his high hopes for the young shortstop.

“When I saw him, he reminded me of a young Derek Jeter,” Towers said at the time. “I was fortunate enough to see Jeter when he was in high school in Michigan and [Didi has] got that type of range. He’s got speed. He’s more of a line drive-type hitter, but I think he’s got the type of approach at the plate where I think there’s going to be power there as well.”

If there was one consistent knock on Gregorius’ game, it was a perceived inability to hit left-handed pitching. That had relegated him into something of a part-time player with Arizona, and Gregorius arrived in New York carrying a .243 average over his three seasons in the majors. He had batted .184 with a .490 OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging percentage) against lefties.

Three years later, while savoring his two homers off Indians ace Corey Kluber in the deciding Game 5 of the AL Division Series, Gregorius said that his confidence had never been shaken—even if it took others longer to come around on his potential.

“A lot of times, guys put a label on a person without letting the person develop,” Gregorius said. “They always predict something, like, ‘This guy can only play defense or this guy can only play offense.’ But you don’t know how hard a guy works to get where he wants to be, to stay where he wants to be, and to keep making adjustments every year to try to get better. For me, I always believed in myself. There’s always people that are going to doubt you. At the end, it’s up to you how hard you want to work.”

Girardi had made the point shortly after the trade that Gregorius seemed to have been stuck with a reputation based upon a small sample size, noticing that the D-backs only gave Gregorius fifty-one at-bats against lefties in 2014, in which Gregorius managed seven hits (.137). The Yankees hedged their bet by keeping the light-hitting defensive whiz Brendan Ryan around, believing that they could have the right-handed hitting Ryan face all of the lefties if necessary.

It was an issue that never presented itself. Jeff Pentland and Alan Cockrell, the team’s hitting coaches that season, said that they discovered Gregorius had been taught to hit the ball on the ground up the middle or to the opposite field in his previous big-league stops. They wanted Gregorius to embrace his latent power, encouraging him to pull the ball to right field more often.

“I think he’s always had bat speed and leverage, God-given,” Cockrell said. “He was able to kind of shorten his swing and more efficiently get the barrel to where it needed to be, and he’s always behind the baseball. He puts himself in a good position to hit, so I saw that coming before I think Didi saw it.”

Hensley Meulens also deserves some credit for helping Gregorius take his swing to the next level. Once a touted Yankees prospect nicknamed “Bam-Bam” who played parts of five seasons in the Bronx from 1989–1993, Meulens operates a camp for professional ballplayers in Curacao during the offseason, where some three dozen athletes gather on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays for morning workouts.

A highly-regarded coach on the Giants’ big league staff who would be one of the six men to interview for the Yankees’ managerial vacancy after the 2017 season, Meulens observed Gregorius in the batting cage and remarked that he had recently helped left-handed hitting shortstop Brandon Crawford improve his performance against lefties. Crawford had batted .199 against lefties in 2013, improving that mark to .320 in 2014.

“We had closed Brandon Crawford off a little bit from leaking in the front side against lefties, and he had great success,” Meulens said. “I told him, ‘What I would try to do is stay in there and hit a line drive toward the shortstop.’ I’m not saying that triggered Didi to hit better against lefties the last few years, but he is a hard-working guy. He knows what information to take from whom and put it into the game."

By 2016, Gregorius was batting .324 against left-handed pitching, the third highest such average by a lefty batter in the big leagues. Naehring was not surprised that Gregorius had been able to make the necessary adjustments to succeed against all pitchers.

“I was never in the camp of, ‘He’s going to be tremendously exposed by left-handed pitching,’” Naehring said. “I thought he had the ability to manipulate the bat barrel and I thought he showed raw power, especially to the pull side, that I thought would play up at Yankee Stadium.”

Gregorius also showed a knack for handling the demands of the post-Jeter era, often deflecting questions about his predecessor. While some feared that the weight of Jeter’s legacy could overwhelm Gregorius, Cashman articulated it another way. In his final season, Jeter had batted .256 with four homers and 50 RBIs in 145 games, and Cashman suggested that Gregorius wouldn’t have to do much to represent an improvement over that diminished version of the captain.

“It’s never going to go away,” Gregorius said. “It’s a game of comparisons. No matter what you do, you’re always going to get compared. Maybe when he played, he got compared to somebody else.”

As the 2015 season dawned, Gregorius was the only player in the Yankees’ starting lineup under the age of thirty, and his inexperience showed. On Opening Day against the Blue Jays, he committed a cardinal sin by being thrown out attempting to steal third base with his team down by five runs, one example in a series of routine fielding errors and baserunning miscues. After getting those initial jitters out of the way, Gregorius steadily improved. A .206 hitter in April, Gregorius batted .232 in May, .258 in June, and .317 in July.

One afternoon in late April, infield coach Joe Espada summoned A-Rod as a guest tutor, with Espada saying that they wanted to help Gregorius anticipate plays better, remain aware of outs, and know when to charge the ball and when to stay back. Once the game’s premier shortstop before agreeing to shift to third base following his 2004 trade to New York, Rodriguez conveyed the importance of a shortstop’s positioning, cadence, and internal clock, predicting that Gregorius would be able to fine-tune those characteristics with experience.

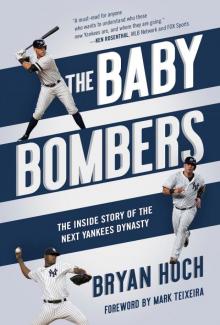

The first shortstop in Yankees history to hit 20 or more home runs in consecutive seasons, Didi Gregorius’s 25 homers in 2017 surpassed Derek Jeter’s club record for homers by a shortstop. (© Keith Allison)

“The abilities are off the charts,” Rodriguez said then. “He’s got the things you can’t teach; incredible range, great arm strength. People forget, he’s only been playing shortstop for eight years. The more he comes out, the more he gets experience, the better he’s going to be.”

After being paired with second baseman Stephen Drew up the middle for most of the 2015 season, Gregorius received an ideal partner prior to the 2016 season when the Yanks acquired Starlin Castro from the Cubs in exchange for right-hander Adam Warren and a player to be named later (who turned out to be Ryan, the free-spirited backup infielder whom Gregorius had made superfluous). Like Gregorius and outfielder Aaron Hicks, who was acquired in a November 2015 trade with the Twins for light-hitting backup catcher John Ryan Murphy, Cashman was attracted to Castro—then twenty-five years old—because of his youth and flexibility, two qualities that the Yankees sorely needed to showcase more of.

Castro had compiled an impressive 991 hits through his first six seasons in the big leagues, but the Cubs bounced him from his shortstop position to accommodate a younger prospect, Addison Russell, who’d be selected as a National League All-Star in 2016 while helping the Cu

bs end a 108-year World Series drought. The deal was consummated in early December 2015, but Cashman’s pursuit of Castro had started months earlier with several pitches prior to the July 31 trade deadline. Unbeknownst to Chicago, the Yankees’ scouts had identified Castro as a player who might benefit from a move to the other side of the bag. When Castro batted .339 with a .903 OPS in 33 games as a second baseman, the shuffle provided a sneak preview that backed the theory.

“Even before the positional switch, we felt by our evaluations that he could be a pretty interesting player over at second,” Cashman said. “Then when the Cubs made the switch, we got confirmation of that.”

Cubs president of baseball operations Theo Epstein told Cashman that he would be willing to move Castro if he was able to finalize a different transaction during the 2015 Winter Meetings, which turned out to be a four-year, $56 million pact with infielder Ben Zobrist. Moments after that deal was finalized, Epstein told Cashman that he was ready to act, and the Yankees agreed to take on the remaining $38 million that Castro was due through 2019. It was a sizable investment, but one of the more supportive voices in Cashman’s ear had been that of Jim Hendry, who’d spent parts of ten seasons as the Cubs’ GM beginning in 2002.

“Starlin had this storybook beginning, playing in the All-Star Game at twenty-one and had 200 hits,” Hendry said. “The last couple of years [in Chicago] after I left, he had some ups and downs. If anybody would have told us at twenty-two or twenty-three that he wouldn’t be hitting around .300 every year with 20 to 25 home runs, it would have been hard to believe.”

Born one month apart in the spring of 1990, Castro and Gregorius comprised the youngest Yankees double play combination since Willie Randolph and Bucky Dent in the 1970s, and they instantly hit it off away from the field. Seemingly competing to be the team’s flashiest dresser (Castro probably won in a dead heat), the twenty-somethings often peppered each other with snarky remarks in English and Spanish from their adjacent lockers.

The easy rapport between the new teammates prompted the team’s in-house “Yankees on Demand” video crew to ask them to participate in a stellar shot-for-shot remake of a scene in the 2008 movie Stepbrothers. Gregorius played John C. Reilly’s part and Castro delivered a version of Will Ferrell’s lines to hilarious results. Had they just become best friends? As Gregorius’ character screamed, “Yup!”

“I feel like he is my brother,” Castro said. “That’s my double play partner, and not only in the field. I think that we’ve got a really good relationship.”

Castro’s comfort level shouldn’t have come as a surprise. His big league mentor had been former Bombers star Alfonso Soriano, who broke in as a power-hitting second baseman and played parts of five seasons in New York before being traded to the Rangers as part of the A-Rod trade in December 2003.

By 2010, when Castro arrived at Wrigley Field, Soriano had shifted to left field and was playing the role of sage veteran at age thirty-four. The eight-time All-Star took Castro under his wing and taught his fellow Dominican how to dress, how to act, and how to play while tuning out the negativity that often comes with competing in a major market. In appreciation, Castro named Soriano as the godfather to his son, Starlin Jr.

“He took me to his house to live with him, and I appreciated that a lot,” Castro said. “I would hang with him every day, work out every day and every morning, just work out with him. He helped me a lot and he taught me how it is in the big leagues.”

Though some of the most recognizable names in Yankees history took their positions in the middle of the diamond, Castro and Gregorius accomplished something in their first year playing together that the likes of Jeter, Randolph, Tony Lazzeri, and Phil Rizzuto never could, becoming the first double play combination in franchise history to each hit twenty or more home runs in a single season.

Few double play combinations around the majors were a tighter fit than the Yankees’ Didi Gregorius and Starlin Castro. “I feel like he is my brother,” Castro once said. (© Keith Allison)

It would take something significant to dislodge Castro from the Yankees’ plans, and that development took place in December of 2017. Despite leading the majors with fifty-nine home runs that past season, reigning National League MVP Giancarlo Stanton was being shopped by Jeter’s debt-laden Marlins, who were desperate to free themselves of the $295 million owed to the slugger through the 2028 campaign. Separate deals with the Cardinals and Giants were agreed upon, but fell through when Stanton told the Marlins he would refuse to waive his no-trade clause to all but four playoff-ready contenders: the Astros, Cubs, Dodgers, and Yankees.

Pursuing a power-hitting outfielder had not necessarily been on the Yankees’ wish list going into the offseason, but it was difficult to turn down an opportunity to add a player of Stanton’s caliber. New York produced the winning offer, obtaining the twenty-eight-year-old Stanton in exchange for Castro, right-handed pitching prospect Jorge Guzman and infield prospect Jose Devers. The Yankees agreed to take on all but $30 million of the fortune owed to Stanton.

“We still gave up talent,” Cashman said. “I appreciate everything Starlin Castro did for us. He was a great pickup for us. A high-character guy. He’s tough as nails. He had a great personality. You never saw him have a bad day. He helped us in that win column in many ways.”

While Gregorius repeatedly said that he did not consider himself a home run hitter, he was one of several young Yankees who credited veteran Carlos Beltran for helping with his plate discipline during their time together as teammates. Perhaps by virtue of patrolling the same patch of Bronx real estate, Gregorius had also seemed to inherit Jeter’s unquenchable thirst for championship hardware.

Despite missing most of April with a right shoulder strain, the 2017 season saw Gregorius set new career highs in runs (73), homers (25), and RBIs (87) while leading the team with 44 multi-hit games and batting fourth in the lineup 42 times. Only the Indians’ Francisco Lindor hit more homers (33) among big league shortstops, but despite the gaudy numbers, Gregorius repeatedly said that his performance could have been better.

“A ring. That’s my goal,” Gregorius said. “That’s why you play the game. Winning is our goal. And if one of these guys doesn’t have that goal, then you need to sit in my locker and talk about it.”

With the help of his lieutenants and some creative thinking, Cashman had stabilized the middle infield by executing a pair of old-fashioned baseball trades. To assemble the rest of the franchise’s next dynasty, the Yankees would have to make bold moves in a challenging domestic and international marketplace.

CHAPTER 3.

Repairing the Pipeline

It was the summer of 2005, and Brett Gardner broke a lengthy stare at the fine print resting in front of him. One of the documents featured the midnight blue flowing script of the New York Yankees’ logo, along with the iconic mailing address at the corner of East 161st Street and River Avenue in the Bronx.

Gardner did not have any particular loyalty to the Yankees at that time; like many in the South with cable television access to the Turner Broadcasting System superstation, his cheering allegiances had been secured by the Atlanta Braves, who played their home games about four hours from his home in tiny Holly Hill, South Carolina. This piece of paper was making a convincing case for Gardner to rethink those rooting interests.

The Yankees were offering Gardner more money than he had ever seen in his life, $210,000, in exchange for agreeing to join the organization as a third-round draft pick. Though Gardner was aware of the team’s reputation of struggling to promote their own young players to the big leagues, the idea of being a member of the farm system sounded a whole lot more appealing than spending his days on an actual farm.

To be clear, the undersized outfielder admired his father John’s devotion and commitment in tending to a 2,600-acre patch of the Palmetto State, where the Gardners coaxed corn, cotton, soybeans, and wheat to emerge from the rich soil. Gardner had helped out his mother Faye and older brother Glen

on occasion, driving a lawn tractor or a combine, but Gardner found the early mornings and long afternoons to be something of a bore.

“It’s pretty much been his life every day for the last thirty-five or so years,” Gardner said. “That’s how I grew up. It’s definitely not the easiest thing in the world to do, but even though it is hard work, it’s something that he enjoys doing and can be rewarding.”

When Gardner laced his spikes on the campus of the College of Charleston in 2001, trying out for the baseball team as a non-scholarship freshman, he stood five-foot-eight and weighed a spindly 155 pounds. Gardner remembers having above-average speed at the time and thought that he did fine when the coaches had him run a sixty-yard dash, but the rest of the tryout was admittedly unimpressive.

“There are only a handful of guys that are going to stand out in an environment like that,” Gardner said. “You run the sixty, you make some throws to third base from right field, and I didn’t have that strong of an arm—still don’t, really, but then it wasn’t as strong as it is now. You probably get ten, twenty swings in batting practice, and I wasn’t going to turn anybody’s head hitting singles over the third baseman’s head.”

After a few days, Gardner had not been invited back by the coaching staff, so he silently dragged his baseball equipment back to Holly Hill. John Gardner had been a minor league outfielder in the Phillies organization in the 1970s, and when he spotted the gear in his home, a note was dashed off to head coach John Pawlowski. Let his son attend practice with the team, the message pleaded. With no promises of playing time in actual games, Pawlowski agreed to let Gardner work out and participate in some of the Cougars’ fall scrimmages. Showcasing his fierce determination, Gardner made the coaching staff take notice by leaving the field with the dirtiest uniform nearly every afternoon.

“We’re definitely both hard-headed,” Gardner said of his father. “I think that work ethic and not taking no for an answer—you try and get the most out of what God gave you. I played with plenty of guys that were way more talented than I am, but guys that maybe didn’t want it quite as bad. I feel like that’s something that not only has gotten me to where I am, but has helped me stay where I am.”

Baby Bombers

Baby Bombers![[No data] Read online](https://i1.freenovelread.com/i2/04/08/no_data_preview.jpg) [No data]

[No data]