- Home

- Bryan Hoch

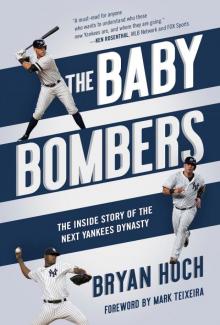

Baby Bombers Page 6

Baby Bombers Read online

Page 6

“Hey, Bird didn’t have the greatest [performance], but trust me, this guy has got the right mentality,” Kmetko told Oppenheimer. “He can slow things down. He’s got a lot of the intangibles we’re looking for.”

By chance, Grandview High’s baseball team made an early 2011 trip to Florida, taking advantage of the Sunshine State’s warm weather as snow blanketed their own diamond. The Yankees sent scout Jeff Deardorff to watch Bird, who still was not drawing a great deal of interest from other clubs; Oppenheimer believed that Bird’s Colorado mailing address likely had kept him off some radars.

In fact, when the left-handed Bird stepped into the batter’s box, Deardorff noticed that he was the only scout who positioned himself for a clear view from the third-base side. He loved what he saw.

“This guy is going to be a monster,” Deardorff reported. “He can hit, he’s got power. The swing is beautiful.”

Later that year, Oppenheimer was on his way to Wyoming for a look at high school outfielder Brandon Nimmo, who would be selected by the Mets in the first round that June. Kmetko urged Oppenheimer to make a detour to Colorado, where Grandview was playing a previously unscheduled game to make up a rainout.

“I get there early on a Saturday morning and he’s taking BP, hitting balls out to dead center and really high. Guys don’t do that,” Oppenheimer said. “Yes, it’s Colorado, but high school guys don’t do that. Left-handed guys, they’re going to pull, hit some line drives. I watch, he’s a big-sized guy, he catches, I’m thinking the arm is good enough—and there’s only two other scouts there. It was an odd deal.”

The Yankees grabbed Bird in the fifth round that June, with a $1.1 million bonus swaying him to bypass a commitment to the University of Arkansas. Oppenheimer said that Bird had done his homework and knew what kind of money he might be able to get three years down the line. At the time, it was believed that Bird would be able to continue catching, but the Yanks also thought his bat was good enough that it would be fine at another position. Bird caught three games in the Gulf Coast League before physical issues prompted a permanent shift to first base.

As it turned out, the Yanks’ biggest find—literally—came in the person of Aaron James Judge, though landing the future unanimous American League Rookie of the Year and runner-up for AL MVP had taken a fair amount of luck. They first spotted Judge in tiny Linden, California, population 1,784, a pinprick of a community about 100 miles northeast of San Francisco that does not have a single stoplight. Linden had made its mark as the self-anointed “Cherry Capital of the World” before a barrage of big league homers in 2017 changed that slogan to “The Home of Aaron Judge.”

The Athletics had been the first organization to take a swing at Judge, calling his name as a high school player in the thirty-first round of the 2010 draft, but Judge had not been convinced that he was ready for the commitment of playing professionally. Though Judge didn’t know it at the time, the Yankees had agreed with that assessment. Kendall Carter, then a national cross-checker for the organization, saw some of Judge’s games at Linden High and reported that he’d seen an athletic specimen who still needed to grow into his body and improve his coordination.

Carter recommended that the Yankees keep tabs on Judge, telling Oppenheimer that the prospect might be something special three years down the line. Judge had played first base and pitched in high school, but when he arrived on campus at Fresno State University, that would have to change. Then the nation’s leading college home run hitter, Jordan Ribera was manning first base for the Bulldogs, so Judge’s choices were the outfield or the bench. Judge had been a three-sport athlete in high school, playing baseball, football, and basketball. Head baseball coach Mike Batesole told Judge that if he could run routes to catch footballs, there was no reason he couldn’t do the same with a baseball.

It didn’t take long for Batesole to recognize that Fresno State had a special talent in Judge, who was named a Louisville Slugger Freshman All-American and the Western Athletic Conference’s Freshman of the Year. Each fall, Batesole organizes a touch football league to help his baseball players maintain their conditioning, with the gridiron running from the right field foul pole across the outfield grass. Then weighing about 230 pounds, Judge dominated from the first snap of his freshman year.

“These are Division I elite athletes, running him down,” Batesole told ESPN. “They run a wide receiver screen. There’s some Barry Sanders happening here. All five guys on the other team are on the ground, squinting and wrinkling their noses, watching him run for a touchdown. I’ve never seen anything like it. My first thought was, ‘Yes! We’ve got one!’ This isn’t a guy that’s just going to play in the big leagues for a year or make an appearance. When I saw that, I was like, ‘We’ve got a freak here. This guy is going to play as long as he wants in the big leagues.’”

Fresno State eventually had to keep Judge out of the flag football games, as Batesole feared that one of his players might injure a knee trying to keep up with him. Though he had the physical attributes to patrol the outfield with grace, questions remained about how a player with Judge’s build would adjust to professional pitching. Scouts find a safety net in having big league comparisons to call upon, and in Judge’s case, there weren’t many players his size who had enjoyed sustained success. Yet Oppenheimer also recognized that players who merited legitimate comparisons to Giancarlo Stanton do not come around the block every week.

The Yankees asked Chad Bohling, the team’s director of mental conditioning, to get a read on Judge. Though other clubs have followed suit in recent years, the Yankees were the first team to interview amateur players instead of issuing written tests, incorporating those assessments into their scouting after hiring Bohling away from the NFL’s Jacksonville Jaguars in 2005. The thinking was that by doing so, bad eggs could be weeded out of the system before they ever had a chance to put on the pinstripes. Bohling flew across the country and spent about an hour speaking with Judge at a restaurant near Fresno State’s campus, returning with a glowing endorsement of the prospect’s mindset and background.

“There was still a long way for him to go, but after that combination of what he was tool-wise, the big kicker was the makeup,” Oppenheimer said. “The makeup set him apart and made him somebody that we thought could reach those lofty projections.”

Judge played left field and right field as a freshman at Fresno State, then center field in his final two seasons, earning a reputation as a solid defender and hard worker whose power still hadn’t translated into game action. Though Judge stole twice as many bases (36) as he hit homers (18) over four years in a Bulldogs uniform, there were glimpses of what Judge would become, including during a memorable BP session during a Cape Cod League showcase at Boston’s Fenway Park in July 2012.

“Very rarely do we get to see draft kids in a major league setting,” Oppenheimer said. “We see them on their high school field or their college field. You put them in that, and all of a sudden, it’s a little bit of an eye-opener. It was a different sound and the ball was going into a different spot than the rest of that group.”

Matt Hyde, the Yankees scout assigned to the New England region and the Cape Cod League, had filed effusive reports on Judge prior to his junior season at Fresno State. So had Brian Barber, a Yankees national scout, who had seen Judge in the lineup for the Cape Cod League’s Brewster Whitecaps on at least four occasions that season.

“You just don’t see guys on a baseball field built like this,” Barber said. “He played center field that day, and I was like, ‘Wow.’ Then you notice how hard he hit the ball. It’s one of those things in scouting, you happen to be at the right park on the right day, and he hit an absolute mammoth home run the day that I saw him. It was like, ‘All right, wow. That’s how superstars hit them.’”

Barber had sized up talent like Judge’s before, albeit from a distance of sixty feet and six inches. The Cardinals had made Barber the twenty-second overall selection in the 1991 draft, plucking him from an Orl

ando, Florida, high school and hurrying him to the big leagues four years later at age twenty-two. Injuries ended his career at age twenty-eight, prompting Barber to join the Yankees organization as a scout for the 2002 season.

It turned out to be a good fit. As a starting pitcher, he’d spent many off-days holding a radar gun and charting pitches from the stands, finding that fresh look at the game fascinating. Barber can still recite the report that he filed to headquarters on Judge.

“I remember it exactly,” Barber said. “I put him as a definite first-rounder the first time I saw him. He did something at the park every day that made you like him more and more. It wasn’t just the power, it was the fact that he was playing center field. You didn’t have any inclination to think that he was going to play center field in the big leagues, but he was a quality defender out there…

“The last piece of the puzzle was, this guy is six-foot-seven with really long limbs and he’s able to keep his swing halfway short and get the balls on the inner half. I played ten years before scouting and when you saw a guy that big, the first thing you try to do is exploit him inside. You couldn’t do that with this guy.”

When the Yankees returned to the Fresno campus for a fresh look at Judge, they saw a player who had traveled light years from those formative years at Linden High.

“Damon Oppenheimer asked me to go see him, and it was apparent that there was a ‘Wow’ factor to him,” said Billy Eppler, who was then the Yankees’ assistant general manager and is now the GM of the Angels. “To see a human being that big, hitting a baseball that hard. He had the ability to manipulate his swing and put together a quality at-bat, time and time again. And how he moved, at that size, playing center field then? I don’t think anybody is surprised with what he’s been able to achieve, with the physical talents as well as the character.”

Judge compiled a monstrous 1.116 OPS and was named as an All-American during his junior season, when many of those at-bats were witnessed by area scout Troy Afenir.

A former first-round pick who appeared in forty-five big league games for the Astros, Athletics and Reds in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Afenir would earn a reputation within the Yankees system as a grinder and one of their toughest graders, but 2013 was his first year scouting the Southern California region. He’d inherited a list of players to see from Tim McIntosh, another former big league catcher who’d left to pursue a scouting opportunity with the Angels, and Afenir crossed the names off one by one. Judge’s size and athleticism awed Afenir.

“When you get a chance to see him put it into action, it was pretty special,” Afenir said. “I remember the coaches always saying that the guys who were the best were the guys who made it look the easiest and Aaron always did that, just from the way he played in the outfield and his natural leadership. Things like that indicated that he had everything that I was looking for.”

There was other top talent in the area, keeping Afenir busy. The Astros were preparing to make Stanford right-hander Mark Appel the first player taken in the draft that June, and Stanford outfielder Austin Wilson would go in the second round to the Mariners. With Appel expected to come off the board well before the Yankees would have a chance at him, Afenir recalls weighing Judge against University of Nevada Reno pitcher Braden Shipley, who would go to the D-backs with the fifteenth overall pick. More often than not, Afenir thought Judge would be the better call.

“I remember [Afenir] telling me, ‘I don’t know exactly what I’ve got here because I’m new to this, but people aren’t going to hit it any harder. They’re not going to hit it any farther, and he’s a really good baseball player,’” Oppenheimer said. “That’s the thing that kept coming out, that he was a really good baseball player.”

On those recommendations, Oppenheimer made a bleary-eyed trek through security at San Diego International Airport early on the morning of February 24, 2013, boarding a flight north to see Fresno State take the field against Stanford University. Judge didn’t do much in batting practice, but he made plenty of noise in the game, going 5-for-5 with three RBIs, including a long home run to left field leading off the seventh inning.

In three years at Fresno State, Aaron Judge hit .346 with 41 doubles, 17 homers, and 35 stolen bases. He was a three-time All-Conference first team selection and a 2013 All-America honoree. (Courtesy of Fresno State Athletics)

“It’s against Stanford, so it’s solid pitching,” Oppenheimer said, “and you’re just sitting there like, ‘Wow. What else do I need to see?’”

Yankees scouts kept tracking Judge, mostly to make sure that he remained healthy and that his performance didn’t dip. Some compared Judge’s agility to that of NBA superstar Blake Griffin, and as Barber colorfully put it, “This wasn’t Herman Munster out there.” Afenir said that Judge’s placid demeanor impressed him even more than the line drives that seemed to rocket off his bat.

“You didn’t know if he had gotten three hits the day before or whether he’d struck out three times,” Afenir said. “He was so consistent with his approach to the game.”

The MLB draft has existed since 1965, but it does not carry the cache of its NBA and NFL counterparts, in part because college baseball does not garner the television airtime that college basketball and college football do. As such, all but the elite high school and college baseball players remain largely unknown to the public until their names are called, though that has changed somewhat in the Internet era.

The sheer size of MLB’s draft also makes it more difficult to track. Big league clubs currently take turns selecting players for forty rounds over three days each June, whereas the NFL draft and NHL entry draft are each seven rounds. The NBA draft lasts for only two rounds. In recent years, baseball has made efforts to entice the same kind of interest that its NBA and NFL counterparts enjoy, televising the first two rounds with live analysis from MLB Network’s studios in Secaucus, New Jersey.

Leading into the draft, Oppenheimer ranked Judge as one of the top collegiate hitters on the board, along with Notre Dame infielder Eric Jagielo and Philip Ervin, a right-handed hitting outfielder from Sanford University in Birmingham, Alabama. The Yankees had done plenty of legwork, as they were in the uncommon situation of making three selections in the first round.

While their first selection was slotted twenty-sixth overall, they had also picked up a pair of compensatory draft picks. The thirty-second pick went to New York as compensation for losing outfielder Nick Swisher, who had signed a four-year, $56 million deal with the Indians. The Yankees also scored the thirty-third pick when right-handed reliever Rafael Soriano signed a two-year, $28 million pact with the Washington Nationals.

There was consensus within the organization about Judge’s appeal, but Jagielo seemed to be a more conventional selection, a left-handed hitter from Downers Grove, Illinois, with legitimate power who would profile well at either infield corner. It was an opportunity to gamble. If the Yankees selected Jagielo at twenty-six, Oppenheimer believed that Judge would still be there at thirty-two, but the veteran talent evaluator doubted they could land both players by trying the reverse.

Operating from a war room decorated with cluttered dry-erase boards and binders of scouting reports on the third-base side of George M. Steinbrenner Field in Tampa, Florida, the Yankees sent word to their draft representatives in New Jersey that they were to use the twenty-sixth pick on Jagielo. Oppenheimer’s heart thumped a few additional beats as the next selections ticked off the board.

The whispered intelligence turned out to be true; the five teams selecting between twenty-six and thirty-two had not been locked in on Judge. Ervin went to the Reds, followed by Rob Kaminsky (Cardinals), Ryne Stanek (Rays), Travis Demeritte (Rangers), and Jason Hursh (Braves).

“I’ve had a lot of guys since tell me that they really liked him and that there was a split camp with their club,” Oppenheimer said. “Some teams had scouts that really liked him and some that weren’t on him. For us, we were lucky in that we didn’t have a split camp.”

Judge was on site at the MLB Network studios, having made his first trip to New York City for the event. His initial read of the Big Apple was that it seemed too busy and hectic for his liking, telling a reporter from the Fresno Bee the day before the draft that he was “not sure if I could ever live here.”

Good thing that the Yankees hadn’t heard that comment. Maybe they ignored it.

“With the thirty-second selection of the 2013 First-Year Player Draft,” Commissioner Bud Selig said, his hands cradling the podium as he leaned into a microphone, “the New York Yankees select Aaron Judge, a center fielder from Fresno State University, Fresno, California.”

Dressed in a charcoal suit with a gray shirt and purple tie, Judge rose from his seat and embraced his father, then enveloped his mother in a bear hug. Judge said that he had spoken with the Yankees two days before that moment, but did not hear much from them on the actual day of the draft, so it had been “a good surprise” when they called his name.

“We thought we knew there was enough hesitancy within the industry, within baseball, that they were a little bit scared of Aaron Judge,” Barber said.

As Judge tried on the pinstripes for the first time, commentator Harold Reynolds said, “I don’t think that jersey fits. This kid is big.” An on-screen graphic then compared Judge to Nolan Reimold, an outfielder who had batted .246 over an eight-year career, mostly spent with the Orioles. It seems in retrospect to be a curious comparison, as Reimold never exceeded 15 homers and 45 RBIs in a single season. In fairness, Judge had connected for only 18 homers in his college career—and six in 388 at-bats over his first two college seasons.

Speaking on a post-draft conference call with members of the New York media, Judge said that he anticipated that the Yankees would move him to a corner outfield spot because it would be easier to cover ground. He also remarked that he was trying to model parts of his game after Giancarlo Stanton—not the first time, nor the last, that comparisons would be drawn between the future teammates.

Baby Bombers

Baby Bombers![[No data] Read online](https://i1.freenovelread.com/i2/04/08/no_data_preview.jpg) [No data]

[No data]