- Home

- Bryan Hoch

Baby Bombers Page 5

Baby Bombers Read online

Page 5

Three years after his first professional at-bats with the Yankees’ Class-A Staten Island affiliate, Gardner walked into the original Yankee Stadium during its final season of service in the summer of 2008, joining a club where Robinson Cano (twenty-five) and Melky Cabrera (twenty-three) stood as the only homegrown position players under age twenty-five. As he watched the Baby Bombers take over the town in 2017, Gardner was impressed by how thoroughly the landscape had changed.

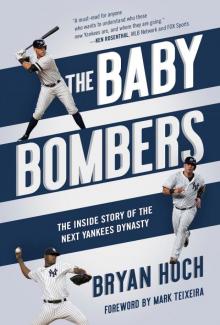

Brett Gardner is one of five players drafted by the Yankees to tally 1,000 hits with the club. The others are Thurman Munson, Don Mattingly, Derek Jeter, and Jorge Posada. (© Keith Allison)

“When I came up, the big-league roster was a roster full of All-Stars and future Hall of Famers,” Gardner said. “There wasn’t nearly as much opportunity and roster turnover as there’s been the last few years. It’s all about opportunity.”

To illustrate his point, Gardner recalled the case of Shelley Duncan, a big-swinging behemoth of a first baseman who hit 43 homers over parts of seven big league seasons with the Yankees, Indians, and Rays from 2007–2013. In another time and place, Gardner suggested, Duncan’s skills should have earned him more of an opportunity with a major league club.

Even the ’17 Yankees could have used a player with Duncan’s skill set as they tried to recover from an early-season injury to first baseman Greg Bird, instead handing most of those at-bats to strikeout-prone slugger Chris Carter. With the Yanks of the late 2000s, Duncan had been blocked by All-Star talent with massive contracts to match: first Jason Giambi, then Mark Teixeira.

Though the Yankees often seemed to address their on-field issues by waving a checkbook rather than developing the answers in-house, Brian Cashman continually stressed the importance of making the roster younger and more flexible. Cashman said that the talent-rich dynasty of the mid-to-late 1990s had been created partially as a result of walking through fire with losing, frustrating teams in the late 1980s.

“Who knew we were actually sitting on a dynasty waiting to happen? None of us,” Cashman said. “All of that talent at the time, it grew into something special. But while that was going on, we were taking hits at the major league level and not making the playoffs on a consistent basis, getting dirt kicked in our face by the ‘Bash Brothers’ and the Oakland A’s dynasty. So I don’t forget those times. From adversity and difficult times, you can grow some great things.”

The Yankees had not endured a losing season since their 76-win 1992 campaign, and as Cashman considered his roster near the midpoint of the 2016 season, he understood that they couldn’t return to the malaise of an era in which pitcher Melido Perez and shortstop Andy Stankiewicz were among the team’s most valuable players. Still, Cashman sensed that many in an underwhelmed fan base seemed to be growing open to the idea of embracing a new direction, urging the club to nudge out a stable of aging veterans who were producing diminishing returns.

Due to changes in baseball’s Collective Bargaining Agreement that were intended to close the financial gap between large market and small market teams, the art of roster construction had changed markedly since the offseason of 2008-09. That year, the Steinbrenner family opened their wallets to upgrade an 89-win team that missed the playoffs, signing CC Sabathia to a seven year, $161 million deal, handing A.J. Burnett five years and $82.5 million, then inking Teixeira for eight years and $180 million.

That spending spree helped to produce a tickertape parade celebrating the organization’s twenty-seventh World Series title, but when the Yankees ripped a page out of that same playbook in the winter of 2013-14, their lavish spending on Carlos Beltran (three years, $45 million), Jacoby Ellsbury (seven years, $153 million), and Brian McCann (five years, $85 million) had not yielded the same results.

They swallowed hard and doubled down by giving pitcher Masahiro Tanaka seven years and $155 million the next winter, and Cashman rationalized it by noting Tanaka’s age. Then twenty-five years old, the right-hander was expected to be on the upswing of his career, despite a heavy workload in Japan. Tanaka dominated in his first turns through the league, winning eleven of his first fourteen big-league starts in 2014 before sustaining a partial tear of his right ulnar collateral ligament. Though Tanaka was able to continue pitching without undergoing Tommy John surgery, his health would be a frequently discussed topic for years to come.

Revenue sharing had been a major factor in the strategy shift, as teams found it more cost-effective to turn to homegrown talent in hopes of reaching the World Series, as the Royals did in 2014 and 2015. The Cubs, the Dodgers, and the Red Sox similarly all built rosters around young cores, supplementing with established veterans rather than relying solely upon them. That was the vision that Cashman held for the future, planting the seeds of a sustainable dynasty by maxing out efforts in the domestic and international player pools.

He had an enthusiastic supporter in managing general partner Hal Steinbrenner, who repeatedly stated his belief that clubs should not have to shoulder payrolls in excess of $200 million to have a chance of winning a championship. The 2009 Yankees are the last World Series-winning club to have spent so lavishly for a title; Kansas City won their 2015 championship with a payroll of $112.9 million, which ranked seventeenth among the thirty big league clubs that year.

To build a winner in that fashion, however, New York would need to improve its ability to discover, obtain, and develop elite talent—something they had lagged behind their competition in doing. Cashman said that incremental adjustments were made along the way, a combination of hiring more experienced scouts, improving the team’s existing personnel, and tweaking the process that the team used. The Yankees also invested heavily in advanced analytics, which they believed would help those in command make safer bets on players.

“We don’t want to walk around with any kind of arrogance that, ‘Hey, we’re the New York Yankees, the most storied franchise in all of sports,’” Cashman said. “It has meaning, but that’s all about the past. It means nothing about the present and the future. We go out of our way to eradicate any arrogance and by doing so, fill that void with a thirst for knowledge and being open-minded to things that potentially exist in the stratosphere.”

One of the answers for the Yankees’ future was located on the unpaved roads of Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic, where a young Gary Sanchez had honed his hand-eye coordination by whacking decapitated doll heads with a broomstick. In his baseball-crazed country, talented young players are quickly snapped up by buscones, or street agents, seeking to cash in by representing the next star who warrants a professional contract.

Sanchez’s older brother, Miguel, spent six years in the Mariners’ minor league chain as a catcher, first baseman, and pitcher, and the Yankees first heard Sanchez’s name at age fourteen. He had been working out in front of representatives from big league teams as early as 2005, when he was thirteen years old.

“At that time, I was in a baseball program, and they would take me to the different tryouts,” Sanchez said. “Sometimes I did tryouts and all thirty teams were there. On other occasions, I would do one tryout in the morning and then have another late in the afternoon.”

Donny Rowland, the Yankees’ director of international scouting, was there to take notes. Rowland had been an infielder for the University of Miami’s powerhouse teams in the early 1980s before playing professionally in the Tigers organization, making it as far as the Triple-A level. Rowland dabbled in coaching before committing the next three decades of his life to the art of identifying and securing talent.

By age sixteen, Sanchez’s body had filled out, with his power and arm drawing even more attention from big league teams. While Sanchez’s catching skills were still clunky and raw, Rowland, longtime pro scout Gordon Blakeley, and Latin American cross-checker Victor Mata each told Cashman that they envisioned Sanchez’s future in pinstripes, pushing the GM to commit the necessary funds that would add his talents to the organization.

“He was a high-profile guy. We didn’t fin

d him; everybody knew about him,” Rowland said. “We saw him a lot, and because we knew it was going to be expensive, we saw him even more. With Gary, back in ’09, it was obvious he was potentially a middle of the order hitter. He had extremely advanced plate actions, swagger, confidence. He took up the whole box. It was his batter’s box––the plate was his. Supremely confident. It was an absolute no-brainer at the plate.”

The Yankees attempted to match Sanchez against the best possible pitching that they could find, scooping up pitchers who had been discarded by other organizations to throw live batting practice. Sanchez raked against all of them. Rowland said that as part of his regular process, he often asks himself what could stop a player from reaching the highest projections, other than injuries. Sometimes it may be susceptibility to a breaking ball, swinging and missing at fastballs, or not generating enough bat speed. None of those registered as a concern with Sanchez.

The only aspect of Sanchez’s game that prompted back-and-forth among Yankees personnel concerned Sanchez’s large frame and unpolished blocking abilities, making some wonder if he projected as a future first baseman or designated hitter. As the Yankees evaluated their 2009 board of the top Dominican prospects, they also weighed gushing reports on sixteen-year-old slugger Miguel Sano. The Yankees saw the bulky Sano as a corner infielder, outfielder, or designated hitter, and Cashman’s lieutenants pushed hard to stress that Sanchez’s future was indeed as a catcher. Even if Sanchez had to be moved, Rowland said that they believed Sanchez would have big league value as a right-handed hitting first baseman.

“We thought that he would be, at minimum, an average catcher with a power arm that could shut down the running game,” Rowland said. “At that point, the interest level was pretty much a no-brainer. Gary ended up on top of our board because we thought he could stay behind the plate and have the same middle of the order offense as a third baseman. Sano is a supremely talented player and highly valuable, but Gary has that same offensive production behind the plate at a premium position. That’s the reason we had him a tick ahead of Sano.”

Third on the Yanks’ list then was a sixteen-year-old centerfielder named Wagner Mateo, and his saga serves as a prime example of the risk involved with signing international prospects. The Cardinals signed Mateo to a $3.1 million bonus but voided the deal when Mateo failed a physical, having been discovered to have 20/200 vision in his right eye that could not be corrected by laser surgery. Mateo settled for $512,000 a year later with the D-backs and batted .230 over five minor league seasons, two of which were spent trying to latch on as a pitcher before hanging it up at age twenty-one.

“During our training sessions, I tell our scouts, ‘When you walk out of that ballpark and you go home to write your report, you have to know that you have nailed the player in an evaluative sense,’” Rowland said. “You’ve nailed him. Your report is spot on. And then, as soon as you hit submit and send the report in, you know that you’ve got a ten percent chance of being right.”

If the Yankees weren’t going to sign Sanchez, they were certain that someone else would. Cashman recalls flying to the Dominican to see Sanchez work out at the Yankees’ facility in Boca Chica, then watching Sanchez pack his bags to immediately go across the street to work out in front of the Mets’ representatives. Cashman had to fight the urge to physically stop Sanchez, whom he recalls as “a man-child,” from leaving the complex.

“I thought I was looking at a college junior physically, rather than a high school sophomore,” Cashman said. “The tool package, you could see the hit ability he had. The cannon arm. The physical tool set was undeniable.”

A decision was made. Though the Yankees extended contract offers to both Sanchez and Sano, they pushed in most of their chips on Sanchez, who agreed to a $3 million signing bonus—the largest that the Yankees had issued to an amateur international player, or any position player, at that time.

“At the end of it all, the Yankees showed the most interest,” Sanchez said. “At the time, I had no money, so it was a great offer by the Yankees.”

Sano turned down a lesser amount—Cashman remembers the number as being $1 million—from the Yankees in favor of $3.25 million from the Twins, with whom he would make it to the majors in 2015 and represent as the runner-up to Aaron Judge at the 2017 Home Run Derby.

Sanchez said that he remembers celebrating at home the night that his professional dreams were realized. He may have splurged on a nice dinner, but there was nothing else of extravagance. It wouldn’t have been permitted. His parents were separated; Sanchez, his three brothers and a sister were raised by their mother, Orquidia Herrera, and grandmother, Agustina Pena, in a small community of Santo Domingo called La Victoria. Sanchez said that his father lived nearby and they spoke on a regular basis.

His mother worked as a nurse, taking multiple shifts per day to pay the rent and put food on the table. Sanchez’s first major purchase was to upgrade his mother’s house in hopes of providing more comfortable living conditions.

“As people, I want to say we stayed the same, but I was able to fix my mom’s house and I was able to help out with other things that we needed help with,” Sanchez said. “It was definitely an improvement in our quality of life.”

Rowland also played a pivotal role in finding a lanky eighteen-year-old Dominican pitcher named Luis Severino, whose athleticism and lightning-quick arm action proved easy to dream on. Raw yet poised, Severino showcased a fastball that sat in the low 90s but had yet to develop the lethal slider that would help him jump to the majors in 2015.

Born and raised in the small town of Sabana de la Mar on the northeast coast of the Dominican Republic, Severino’s long march to the big leagues had started around age ten or eleven, when his father taught him how to grip a curveball and make it spin. Around that time, Severino’s father also purchased his son’s first Yankees cap; it was his most prized possession, and Severino said that he tried to keep it as clean as possible while wearing it daily.

Though Severino seemed to have some pitching chops in his early teens, he lacked the velocity to make a big-league scout pay much mind. In an interview with The Players’ Tribune, Severino recalled that his first tryout had been with the Braves at age fifteen, when Severino had barely been able to exceed 80 mph with his fastball. Like Sanchez and countless others in the Dominican, Severino hoped that baseball would ease his family’s financial strain.

He left home when he was seventeen, traveling about three hours east to pursue better training at an academy in Bávaro, a tourist area of Punta Cana. While there, Severino recalled attending as many as five tryouts in a week, hoping to catch someone’s eye. A major advance in his strength and endurance training came when a coach at the academy instructed Severino to begin running for thirty minutes each morning, then to play long toss with softballs instead of baseballs. Two weeks later, Severino’s fastball had reached the low 90s.

That was enough to draw interest from the Marlins and Rockies, but when scout Juan Rosario introduced himself with a business card that bore the Yankees’ top hat logo, Rosario jumped to the front of the pack. In addition to that well-worn cap with the interlocking NY, Severino had imagined the sandlot down the street from his home to be Yankee Stadium, and he considered Robinson Cano to be his favorite player.

“Sevy blossomed, and Rosario was all over it,” Rowland said. “They blew my phone up and I ran down there. He was a great athlete and had an unflappable look to him. The second time I saw him, he was sick as a dog, throwing up between innings, gutting it out. He was 89-93 mph with a flash of a wipeout slider.

“If he were sixteen when we were watching him, he would have gotten $1.5 million or $2 million. I loved the stuff—demeanor, confidence, athleticism. I asked our scouts, ‘Who would not sign this guy right now?’ Everyone said we had to sign him. So I said, ‘Don’t let him out of the complex.’”

Rowland personally cut the deal in the dugout that afternoon, settling at $225,000 before Severino was sent to make his prof

essional debut in the Dominican Summer League.

“We negotiated, played the ladder game with each other, and I said: ‘Look, he’s going to be eighteen in April. Let’s get this done. He needs to start pitching,’” Rowland said. “Sure enough, he wanted to be a Yankee.”

While Rowland headed the international scouting efforts, director of amateur scouting Damon Oppenheimer and his team of scouts and cross-checkers were responsible for scouring the domestic high schools and colleges for talent. A catcher drafted out of the University of Southern California by the Brewers in 1985, Oppenheimer’s playing career had stalled after seventeen hitless at-bats for Class-A Beloit, leading him into a scouting role with the Padres. Oppenheimer was hired by the Yankees in 1994 as a cross-checker, overseeing a group of amateur scouts.

The Yankees first spotted Greg Bird at Grandview High School in Aurora, Colorado, which fell under the territory of scout Steve Kmetko. While Colorado is generally not a mecca for high school position players, Grandview had become a popular destination for teams performing their due diligence on right-handed pitcher Kevin Gausman, who would be selected in the sixth round of the 2010 draft by the Dodgers before opting to attend Louisiana State University. Two years later, the Orioles made Gausman the fourth overall pick in the nation.

In August 2010, Kmetko followed Bird to Blair Field in Long Beach, California, for the Area Code Games, a six day tournament showcase that features approximately 200 of the top players in the country. Bird dressed in the uniform of the Cincinnati Reds, as did every prospect from the states of Colorado, Nevada, and New Mexico. At the time, Bird wasn’t even the most touted catcher on his team––those honors went to Blake Swihart, a future first-round pick of the Red Sox. A fair showing during the games didn’t do much to distinguish Bird from his competition, but Kmetko urged the Yankees to stay on him.

Baby Bombers

Baby Bombers![[No data] Read online](https://i1.freenovelread.com/i2/04/08/no_data_preview.jpg) [No data]

[No data]